Ancient Egyptians welcomed childbirth with ritual, using medico-magical spells, amulets, and various other objects to help ensure the survival of mother and child.

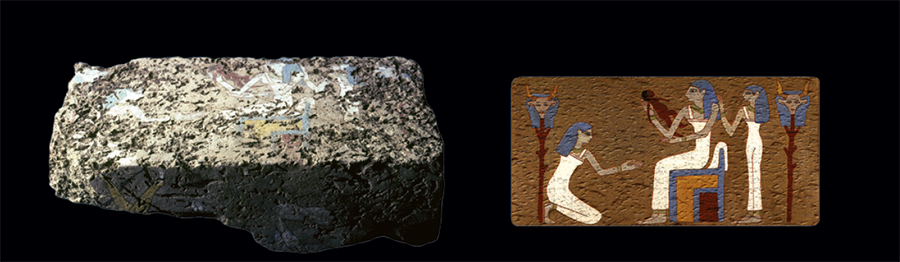

Objects used in childbirth rituals took many forms. For example, a Middle Kingdom (2055–1650 BCE) magical birth brick discovered by the Penn Museum in South Abydos—used to support the mother during labor—depicts images of protective demons as well as a scene of a mother holding her child, flanked by midwives (see Expedition 48.2 [2006]: 35). Such imagery also occurs on contemporary Egyptian ivory birth wands, which functioned to protect newborns.

Museum Object Number(s): 29-86-583

Female Figurines and Model Beds

Figurines that may relate to birth and fertility include “bed figurines,” which depict a nude woman on a bed (sometimes shown with a child) and “model beds,” which do not have human figures. Slender, nude female figures also occur on two-dimensional votive beds—objects dedicated to temples and shrines. The model beds range from simple beds that sometimes preserve painted designs to beds with molded decoration. While previous typologies of Egyptian figurines list the woman-on-a-bed style as having lasted from the New Kingdom (1550–1069 BCE) to the Third Intermediate Period (1069–653 BCE), the Penn Museum has 64 unpublished examples of such figurines, primarily from Memphis, dating to the Greco Roman period (332 BCE–395 CE). They are, thus, the latest known examples of this special type of figurine.

Unfortunately, the records from the Coxe excavations of the late 1910s to 1920s that uncovered the Museum’s figurines are unpublished and do not discuss the objects in detail, so reconstruction of the archaeological contexts of the material proved necessary. Previous theories suggested that these bed figurines were “concubine figures,” they represented a divine mother, or that they were ritually broken to ward off evil spirits. However, new evidence suggests that Egyptians intended these figurines to be used as aids in fertility and birth, both in life and the afterlife.

Flat-backed and model bed figurines depicting females with and without a suckling child have been found throughout Egypt.

Museum Object Number(s): 29-71-817 / 29-71-795 / E119

Concubines of the Dead and Other Theories

When 19th century excavators first found bed figurines in tombs, the nudity of these objects was immediately noticed. From this observation, the initial interpretation was that they represented “concubines,” who would sexually stimulate the deceased male. Specific Coffin Text spells do indeed discuss the deceased as capable of copulation, just as in life. However, bed figurines have also been found in the tombs of women and children, as well as in temples and town sites. None of the women are in obviously sexual poses. Likewise, this theory does not account for those bed figurines that depict a child as well, which otherwise do not differ from those of just the woman.

The “divine mother” theory has been offered to explain bed figurines and flat-backed figurines that include children. This “divine mother” may represent Hathor, goddess of fertility, or Isis, mother of Horus. This explanation is partly based on the Hathoric wigs on a number of the figurines and it supposes that female figurines with children are different in function from those without children. Those who believe the divine mother interpretation suggest that childless figurines functioned as charms for sexual fulfillment for women. This does not explain the presence of these figurines in male graves as well as female graves.

Museum Object Number(s): 29-86-605

The third interpretation suggested that the figurines were ritually broken to ward off evil spirits. Egyptologist Elizabeth Waraksa recently proposed that female figurines, with or without children, served as execration objects that diverted harm away from mother and child to the objects, which were then broken to render threats inert. The objects, mostly in terracotta, would be easy to break, and some ancient texts seem to support this theory. A snake spell in Papyrus Turin 54003, dating to the First Intermediate Period, mentions a “clay [figurine] of Isis” used in this manner. Another passage, a stomach ache spell from Papyrus Leiden I 348, from the New Kingdom, discusses a portable representation of a goddess in clay: “As for any of his suffering in the belly, the affliction shall go down from him into the female figure of Isis until he is healthy.” However, excavators have found a number of bed and flat-backed figurines intact and Kasia Szpakowska and Richard Johnston’s experiment with the breakage of terracotta cobra figures demonstrates that deliberate breakage is difficult to prove. Also, this does not explain those bed and flat-backed figurines in limestone or faience, which are stylistically the same as those in terracotta.

Fertility and Birth

The most compelling hypothesis to explain the bed figurines and the model beds is that these objects aided in matters of fertility and birth. The occurrence of these objects in towns (domestic contexts), temples, and tombs indicates broad usage, which may suggest that they relate to various stages in the human reproductive process from conception to post-birth recovery. The vast majority of the Penn Museum material was found in the temple storerooms of one of the Greco- Roman Period temples at Memphis, while those from Dra’ Abu el-Naga were discovered in tombs. Furthermore, much of the imagery of the figurines and bed models parallels Egyptian fertility iconography.

This birth brick (left) from South Abydos, Egypt, was used to support the mother during labor. The reconstruction (above) shows a scene of a mother and a newborn sitting on a throne. Images from Expedition 48.2 (2006), page 35. Painting by Dr. Jennifer Houser Wegner. Photograph by Elizabeth Jean Walker.

Museum Object Number(s): E482

Museum Object Number(s): E12548

Birth Deities and Iconography

Egyptians conducted fertility and birth rituals both for this life and for rebirth in the afterlife. A bed figurine from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (object number 72.739) depicts the birth deities Taweret and Bes. Bes also occurs as a tattoo on the thighs of women on some bed figurines. Depictions of these two deities appear in New Kingdom wall paintings above domestic altars in Amarna and Deir el-Medina, as well as on birth wands, which protected infants in life and were later placed in tombs to provide protection in the afterlife. While birth imagery occurs on many objects, the iconography seen on the more decorated bed figurines and bed models—such as snakes, Convulvus plants, and mirrors—is most similar to the scenes depicted on New Kingdom ostraca from Deir el-Medina, where a woman suckles her child under a structure made from plants. Such structures are not seen outside of bed figurines and ostraca, indicating they may have been exclusive to the birth process.

As in most bed figurines, the ladies wear perfume cones and jewelry, such as large spherical earrings, collar necklaces, and girdles. The snake might represent a kerket, a protector spirit of a place, in its role as a fertility guardian, or it could refer to scenes of Isis and Horus flanked by serpents. The woman on the ostraca appears in two different ways: on a stool suckling her infant, and on a bed with a child on her lap or lying beside her. The latter, due to the emphasis on servants offering mirrors and ointments, supposedly represents the celebration of purification, which certain texts indicate took place 14 days following childbirth. The highly elaborate bed models, with Bes frequently decorating the posts, are paralleled in the beds depicted in a number of the ostraca.

Museum Object Number(s): 29-71-778

Do the scenes on the ostraca contain sexual references? Louis Keimer has argued that these women are marked as prostitutes because tattoos of Bes appear on some of them. Tattoos of Bes also appear on women in the bed figurines and on female musicians in tomb wall paintings. No evidence exists to support this assumption about tattoos and prostitution in ancient Egypt. This association of Bes with prostitution also ignores the main role of Bes as a protector of women and children in childbirth. Bes even replaces the woman on one of the bed figurines (see PM object 29-71-778, page 43). The tattoos are more likely connected with fertility and birth, as is the rest of the iconography of the scenes.

Excavators have found flat-backed figurines on top of bed models in some temples and domestic shrines. Women employed beds for recovery, since no evidence suggests use during labor. However, some flat backed figurines appear too small for the elaborate beds, the Museum beds from tombs in Dra’ Abu el Naga do not accompany figurines, and no beds are known from the Greco-Roman period. The scenery on molded bed models may relate to Old Kingdom (2625–2130 BCE) tomb scenes of plucking papyrus and New Kingdom erotic symbolism. The former had associations with Hathor, with captions stating that the woman “pulls papyrus for Hathor,” and their location near scenes of wine, dancing, and singing, also connected with the goddess. Certain elements depicted on bed models, such as lute-players (also depicted in tomb scenes) and the Bes figures, suggest rebirth. Thus, these bed models on their own could commemorate birth, celebrate fertility, or serve as protection of a child, with their occurrence in tombs implying continued use in the afterlife.

Museum Object Number(s): E11816

Carved from hippopotamus tusk, this wand was used to draw a circle around the place where a woman was to give birth or nurse her infant. Nine magical figures, including Taweret, the goddess of childbirth, are represented. 1938–1739 BCE, 12th Dynasty, Egypt.

Museum Object Number(s): E2914

Whether used together or separately, the imagery on bed figurines, flat-backed figurines and bed models suggests that these objects may have helped with fertility and childbirth. Those desiring or expecting a child would have presented them at temples as votive offerings, especially for Hathor, and kept them in household shrines with the hope of successful procreation or birth. In the afterlife, these figurines appear to have served a similar purpose for the deceased, ensuring rebirth. As the latest examples discovered to date, the Penn Museum figurines demonstrate the survival of this tradition. The context of most of the Penn figurines—within a Greco-Roman temple in Memphis—indicates they likely served as votive offerings.

Charlotte Rose is a Ph.D. candidate in Egyptian Archaeology, Graduate Group in Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at Penn.

Acknowledgments

This article would not have been possible without access to Penn Museum Egyptian storage and the Museum Archives. I would like to thank Jean Walker and Dr. Jennifer Wegner for granting me access to the figurines. Alessandro Pezzati and Eric Schnittke provided very helpful archival material, allowing me to research the context of the finds. Guidance from Dr. Josef Wegner and Dr. Jane Hickman also aided me tremendously.

For Further Reading

Keimer, L. Remarques sur le tatouage dans l’Égypte ancienne. Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 1948.

Pinch, G. Votive Offerings to Hathor. Oxford: Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum, 1993.

Szpakowska, K., and R. Johnston, 2016. “Snake Busters: Experiments in Fracture Patterns of Ritual Figurines.” In Mummies, Magic and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Multidisciplinary Essays for Rosalie David, edited by C. Price, R. Campbell, A. Forshaw, A. Chamberlain, and P. T. Nicholson, pp. 461-475. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016.

Teeter, E. Baked Clay Figurines and Votive Beds from Medinet Habu. OIP 133. Chicago: Oriental Institute, 2010.

Waraksa, E. Female Figurines from the Mut Precinct: Context and Ritual Function. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 240. Fribourg; Göttingen: Academic Press; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2009.