PALMYRA1 in the desert is a magnificent ruin, a dead city, only known in our MUSEUM through some funerary monuments; a small but representative collection of fifteen busts and reliefs brought back by Dr. John P. Peters from Palmyra in 1890. They well deserve, after so long a span of time, a little attention, as most of them are portraits and bring vividly before our eyes rich merchants and noble ladies of Syria living in the second and third centuries after Christ and contemporary with that fascinating period of history when a woman, that intrepid warrior and astute politician, Zenobia, queen of Palmyra, could match in the East the fortunes of Rome, and from her capital in the desert command an empire extending from Egypt to Asia Minor and including Syria, Arabia, and Mesopotamia.

The traveller who leaves Tripoli, the blue waves of the Mediterranean, the vineyards and olive trees, to reach, beyond the rough pass of the Lebanon encumbered with basalt boulders, the high ground of Horns—the ancient Emese—and from there the silent immensity of the desert, has a delightful surprise at the end of his long journey, when the last bluffs of the limestone hills seem to open and display to his eyes the gate, the stately funerary towers, the long colonnades, and the temples of Palmyra. The setting sun puts golden touches on the rosy cream of the stones, so clear and warm that they seem to have been cut only yesterday.

Museum Object Number: B8904

Image Number: 8041

All here spells Graeco-Roman art and culture: the triple arch of the triumphal gate at the entrance of the main street, the high Corinthian columns, in places still supporting their stone architrave, and above all the great Bel temple. Its shrine has survived plundering, earthquake, and destruction. It still stands up, 60 m. long by 31.50 m. wide, with its splendid doorway, 10 m. high, and its row of Corinthian fluted columns. Only the bronze ornaments which adorned their capitals have disappeared. The shrine itself stands in the middle of a vast courtyard, 235 m. by 235 m., enclosed by a high wall, and once lined with a forest of 390 Corinthian columns, disposed, except towards the west, in a double row. A stone console fixed in each column at about two thirds of its height supported once a statue of some great citizen. A stairway, 37.50 m. wide, gave access to this magnificent court through a porch with columns and three gates adorned with bronze doors.

And yet the desert seems to have put its stamp forever on the ruins. More than half of the great court is destroyed and the rest is crowded with the miserable mud houses of an Arab village. The very shrine of Bel has been transformed into a mosque. Nomads pass unheeding below the memorial inscription engraved on the south wall in the second century A.D., by order of the Senate and the people of Palmyra, to two citizens, cousins “who revere the gods, love their country, and are famous for their generosity, and who have, besides, made at their own expense the six bronze gates of the great portico of Bel.” Who remembers today these two, Iarhibole and Auida? And yet Nicanor, the Alexandrian Jew, is still famous for the single bronze door with gold and silver ornaments which he gave to the temple of Jerusalem built by Herod shortly before the time of Christ.

The two springs which nourish the palm trees, created the oasis, and first tempted the ancient settlers of Palmyra still give clear water and run across the ruined city from west to east to lose themselves in the sands. One issues from a fair cave on the western hill as a beautiful stream three feet by one, the other passes, in an aqueduct, underground. Long lines of Arab women go from the village to the stream in the morning, balancing copper or earthen jars on their heads, to bring home the daily supply. Who cares for the solemn decree of the Senate in the second century A.D., which leased the water of the two springs, the spring Ephca and the spring of Caesar, for eight hundred denarii—about 120 dollars—a high price, and which must have entitled the lessee to the yearly use of water for irrigation, bathing, and perhaps the watering of the long lines of camels of the caravan owners?

Museum Object Number: B8905

Image Number: 8042

And yet the decree was inscribed in the two languages—Ara-mæan and Greek—in common use at Palmyra in the second century A.D. on a large slab of stone, 4.80 in. by 1.75 in., erected in front of the temple of an infernal god, “the chief of the chained ones “—Râbasirê The stone is preserved today in the Museum of the Hermitage in Russia. It was discovered in 1881 by a chance visitor to the ruins, the Armenian prince Abamelek Lazarew, who saw a corner with a few inscribed lines sticking out of the ground halfway between the stream and the temple of Bel. The vicinity of the infernal god may have added its solemn sanction to the decree, which bore the general title: “Custom tariff of the trading post of Hadriana-Tadmor and of the springs Ælius Cæsar.” Tadmor is the Aramæan name of Palmyra, also called Hadriana after the visit of the emperor Hadrianus in 129 A.D.

Nothing so well as this inscription, with its detailed tariff regulations, could bring near to us the intimate life of the busy commercial community and reveal the daily movement of men, animals, merchandise, the continuous train of asses, the caravans of camels, the bustling crowd of traders, publicans, lawyers, brokers, magistrates, passing and pressing under the long porticoes which even now arouse our admiration. The animated Sûq of Baghdad, or the Galata bridge must offer a good modern picture of it. Through the inscription we become familiar with the city administration, its senate with president, secretary, two archons, and a council of ten. But we shall do better to listen to the opening sentences and the venerable words of the ancient text.

“Decree of the Senate. On the 18th of Nîsan, 448 [April 18th, 137 A.D.], Bonnê, grandson of Hairân, being president, Alexander, son of Alexander, grandson of Philopator, secretary of the Senate and the People, being secretary, Maliku, son of Ulaii, grandson of Moqîmu and Zebîda, son of Nesa, being archons, the Senate, being assembled in ordinary session, has decided as follows:

“As in former days many taxable articles were not inscribed in the law, but were taxed according to custom, because it was written in the contract of the tax farmer that he would collect according to law and custom, and since concerning these articles quarrels many times arose between the merchants and the tax collector;

Museum Object Number: B8912

Image Number: 8046

“The Senate has decreed, that the archons and the council of ten shall examine all that is not included in the law, shall include it in the new lease and that the tax as fixed by custom shall be inscribed after each article. When the farmer has ratified the lease, it shall be engraved with the old law on the stela standing before the temple of Rabasirê. The archons in office, the council of ten, and the syndics shall take care that the tax farmer do not exact from anyone anything above the tariff.”

Without its trade, Palmyra, lost in the desert, far from the great political centers and difficult of access, could have secured to its inhabitants a large independence but not the enormous riches which enabled them to build the glorious monuments still covering the ground. Trade, import and export, made the fortune of Palmyra and brought about an incredible prosperity, which exalted beyond measure the pride of the native rulers, excited the suspicions and cupidity of the Romans, and caused the definitive ruin of the city in 273 A.D. The fortune of Palmyra hung on the fact that it was the main emporium on the caravan road by which goods from Persia, India, and the Far East were carried towards the Syrian coast and the rest of the Roman Empire. The expedition of Alexander had thrown open the roads of trade by land and sea. After his death Palmyra with all Syria fell to the lot of Seleucus and his successors. The prosperity of Antioch, their magnificent capital, contributed greatly to the development of Palmyra’s trade. But it was only after Syria had become a Roman province in 64 ac. that this trade reached its largest extension, stimulated by a growing taste for eastern luxuries in the rest of the empire. Palmyra itself remained a long time outside of the limits of the conquered province —Pliny the Younger writes that the city “preserved its independence between the great empires of Rome and the Parthians, who, when they go to war, always first try to enlist it on their side.” Antony had formerly sent his soldiers to plunder it, giving as pretext the suspicious attitude of its inhabitants on the border between Persians and Romans, while he was in reality only moved by greed. But the Palmyrans, warned in time, fled with their riches beyond the Euphrates and left to the Roman troops an empty and inhospitable city.

While not mentioned in the war of Trajan against the Persians, Palmyra was probably drawn about that time—A.D. 115—into close relations with the Roman Empire, or was even incorporated into it. Hadrian visited it in A.D. 129, on which occasion the city took the name of Hadriana. The local tariff promulgated by the Senate of Palmyra in A.D. 137 shows that the Roman authority fully controlled the municipal administration. The tax collector appointed by the city accepted his contract from the prefect of the province. In case of conflict anyone subject to the tax could apply to the juridicus, the Roman magistrate resident at Palmyra. About the same time the city supplied the armies with auxiliary troops, especially archers, for Palmyra was famous for its bowmen. Inscriptions in the Aramaic language and the Palmyrene script, which are due to some of its sons serving in distant parts of the Empire or to some of its merchants following the Roman armies, have been found in Rome, Egypt, Algeria, England, Hungary, and Rumania.

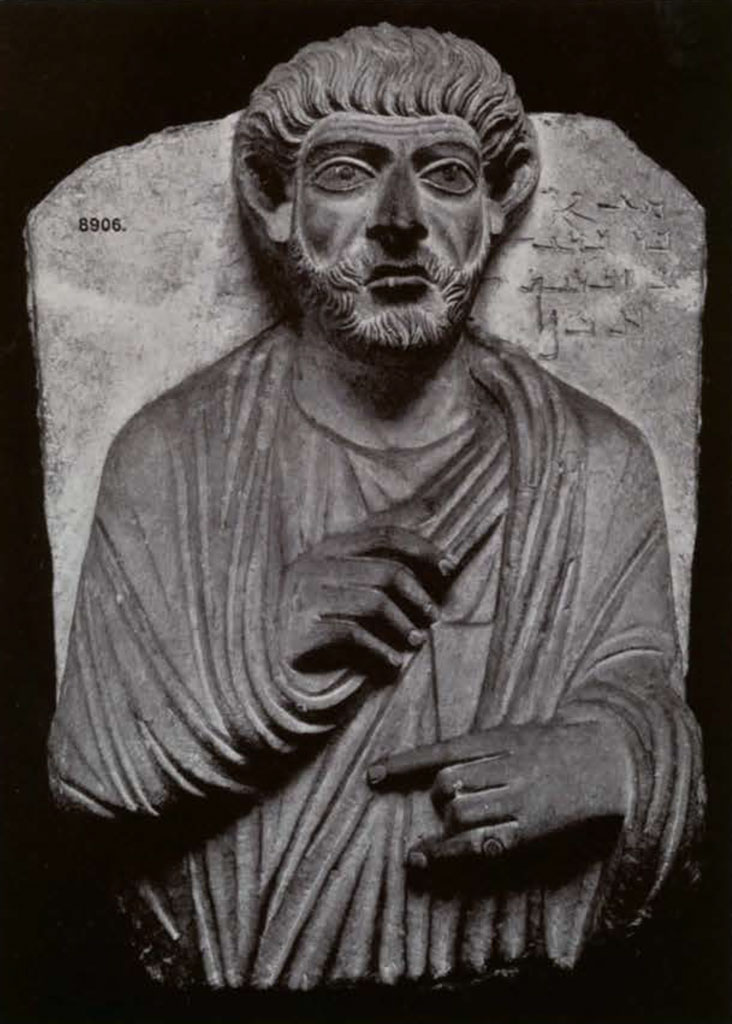

Museum Object Number: B8906

Image Number: 8043

Palmyra was definitely made a Roman colony under Septimius Severus and shortly after Caracalla became associated with him in the empire, about 200 A.D. Severus Alexander, marching against the Persians, passed through the city, and his general Rutilius Crispinus sojourned there a while. If anybody remembered that passing of the Roman legions, it must have been that Julius Aurelius Zabdila, to whom the Senate and the people of Palmyra erected a statue—A.D. 242—because, says the inscription still preserved on the console bereft of its statue, “he was strategos of the colony, when the divine Alexander Caesar arrived. He was in office when Crispinus, the prefect, came, and several times when the legions arrived. He was head of the market. He spent largely. He was honest. Therefore the god Iarhibol “—a sun god like Apollo—” and Julius Priscus testified that he loved and fed his city. Therefore the Senate and the People have erected this in his honor.”

Zabdila evidently received honorable mention from the god through an oracle and from the Roman prefect for undertaking expenses. Another prominent citizen, Malê son of Iarhai, a century before had been rewarded in the same way by a statue placed at the entrance of the temple of Baalsamîn, because, “When the divine Hadrianus came, he gave oil to the citizens, to the troops, to the foreigners who accompanied him. He supplied the camp with all requisites. He built the Temple, the pronaos with its decoration in honor of Baalsamîn . . .” The little temple with the six columns of its porch, is still standing and is one of the best preserved in Palmyra, a memorial to the public-spirited Malê, who spent his wealth for the honour of his native city.

In ancient cities, as today, it was the burden and pride of rich citizens to maintain their state and its gods, to be rewarded by public fame and the honour of a statue. We are not surprised to hear that they had served the gods well, perfectly fulfilled the function of symposiarch or chief priest of BM, endowed a sacrificial foundation or the perpetual maintenance of the senate, presented a bronze censer, or erected six columns. But we are more interested to learn that Nesa was a successful caravan leader according to the merchants who came back with him from Phorat and Vologesias. Marcus Ulpius Iarhai, too, was a great man, who in many ways assisted the caravan returning from Charax Hispasina under the guidance of Zabdeateh. Now Vologesias, Phorat, and Charax are three cities of lower Mesopotamia which in the early Christian centuries were the main entrepots and harbours on the caravan road for the goods of Persia and the Far East coming towards Palmyra. Vologesias was built on the Euphrates by Vologese, who was king of the Parthians at the time of Nero, below Babylon and not far from Kufa. The merchants from Palmyra had here a trading establishment and a temple to their gods. Phorat was built on a small hill near Basrah, which is today the best harbour of Iraq on the Persian Gulf. Charax, the capital of Characene, was restored in B.C. 200 by the Prince Hyspaosine at the junction of the Tigris and the Elæus, on the site of the present Muhamerah. The organization, direction, and upkeep of the caravans between Palmyra and the Persian Gulf was a very important business attended by many difficulties. The journey lasted about two months, during which the feeding of a large number of camels and men and their protection against the nomads had to be assured.

Museum Object Number: B8902

Image Number: 8039

We are anxious to know what the caravans transported and to what kinds of goods the tariff solemnly decreed by the Senate applied. As a rule a camel’s load is the load of two asses, and four camels’ loads make a car load. A car load will pay four times the tax of a camel, an ass only half. Ten times a Roman as makes a denarius, worth about 15 cents. Here is a schedule of Palmyrene trade and taxes:

Slaves.—Imported to Palmyra: 22 denarii. Sold within a year: 12 d. ; after a year, 10 d. Exported, 12 d.

Dried foodstuffs, like dried fruits, pistachios, and other nuts, beans, pine cones, straw, hay, and other unspecified goods. Camel’s load, import or export, 3 d. Ass’s load, import or export, 2 d.

Purple.—Dyed fleece passing from Phoenicia to Persia. Import or export, 8 asses.

Perfumes.—One of the main objects of trade. There were two qualities. The best was sold in small long-necked alabastrons often bearing the name of the perfume maker. The common sort was sold in kid skins. Camel’s load, alabastrons, import, 25 d., export, 13 d.; kid skins, import, 13 d., export, 7 d. Ass’s load, alabastrons, import, 13 d., export, 7 d.; kid skins, import, 7 d., export, 4 d.

The export rate is 50 per cent below the import rate, perhaps to meet the competition of the Nabatæan trade which brought into the Roman Empire spices and perfumes from Arabia. Palmyra controlled the Indian trade.

Oil.—Fine olive oil. Camel’s load, four goatskins, import, 13 d., export, 13 d.; two goatskins, import or export, 7 d.: ass’s load of two goatskins, import or export, 7 d.

Fat, in goatskins. Camel’s load and ass’s load as above.

Salted foodstuffs, chiefly fish from the lake of Tiberias, dried and salted. Camel’s load, import, 10 d., export, 6 d.

Saddle animals, mules.—Tax rate not preserved.

Flocks and herds.—Per sheep and camel, import and export, 1 as.

Perfume dealer’s monthly licence, 2 asses.

Prostitutes were taxed monthly by one of their acts, as fixed in Rome by Caligula, 1 d., or 8 or 6 asses.

Monthly shop licence, 1 d.

Skin, imported or sold, 2 asses. Camel skins were free of tax and were used as tarpaulins for covering the goods.

Water of the two springs, mentioned above, 800 d. A very high price.

Harvest of new crops not yet dried, might apply to barley, straw, or grapes. Camel’s load, 1 d.

Pack animals, even when not loaded, 1 d., as fixed by Cilix, a farmer of the taxes, enfranchised by Cæsar.

So much for the old law. The new law of Palmyra maintained or increased the tariff.

Dried foodstuffs, 4 d. instead of 2.

Purple, 4 d. instead of 8 asses.

Salt from the salt lake about one mile and a quarter from the city. The lake is about three miles long by one mile wide. Even today most of the salt consumed in Damascus, Horns, and their territory comes from here and is probably dealt with according to a single uninterrupted tradition. Per modius, a large bushel measure, 1 as. The amount of salt was measured and the tax paid on it before its sale by the farmer. The new law rules that the salt shall be sold on the market, and that the buyer shall pay the tax of 1 as.

Butchers.—Per slaughtered animal, 1 d.

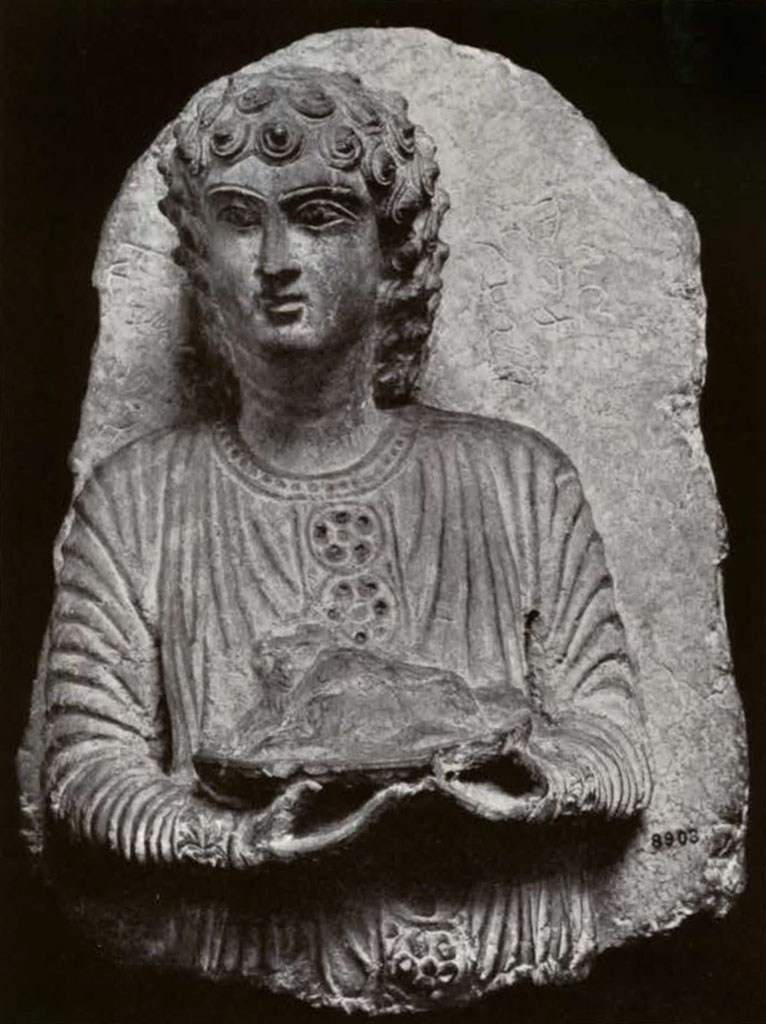

Museum Object Number: B8903

Image Number: 8040

Whatever the importance of this local tariff might have been in 137 A.D., Palmyra in the third century had grown into an enormously rich city. Prosperity fostered the spirit of independence, and led to rebellion. The stern rule of the Roman master was always resented by this mixed Græco-Aramæan population. He represented the foreign domination imposed by military power. There is scarcely a Latin inscription among the seven hundred and more coming from Palmyra. The proximity of the Persian armies beyond the Euphrates was a great inducement for Oriental duplicity, which would break into open revolt as soon as the strength of the Roman Empire seemed to weaken on other frontiers. The tragic story of Queen Zenobia and the destruction of her capital at the hands of the Gallic legions reads like a story of yesterday.

Zenobia, whose real name was Septimia Batzabbai, daughter of Antiochus, or, in Aramæan, Halîphi, came to fame and power after the death of her husband Odeinat, murdered at Emese in 267 A.D., with his eldest son Hairan, by Mœonius, one of his relatives. Odeinat’s father was already a “prince of Palmyra,” his grandfather was raised to the dignity of Roman Senator, he himself had received the title consularis in A.D. 258. He was one of the most important political figures in the East, with a noble tradition behind him. As the Roman power declined, his star was destined still to grow, for his good or bad fortune. The following year, A.D. 259, the Emperor Valerianus fell a prisoner into the hands of the Persians, who plundered Syria and Cappadocia and took Antiochia. Odeinat at the head of the Palmyrene and Syrian troops tried to cut off the retreat of Sapor’s army and forced him to recross the Euphrates. In those stirring times when emperors were rising to power and passing in quick succession, he supported Gallienus and ordered the death of a pretender, Quietus, son of Marcienus. As a reward, he was made dux of the Roman troops in Syria. But his ambition knew no limits. He called himself king. In a two years’ war against the Persians he captured Mesopotamia, but failed to take Ctesiphon, the Persian capital on the Tigris. He was made Imperator and corrector of the whole province. His authority extended over all Syria between Egypt and Asia Minor.

His sudden death left his widow, Zenobia, sole mistress of her destinies. She at once assumed power in the name of her younger son, Vahballât. Gallienus refused to the young prince the titles given to his father and even tried to recover Syria, but the prestige of Rome received another blow when his general, Heraclianus, was defeated by the troops of Palmyra. The next emperor, Claudius the Second, while refusing to acknowledge Vahballât as the representative of Rome, was too busy on the northern frontier to undertake a new campaign in Syria. Zenobia at once took advantage of the opportunity to fortify her son’s dominion. Two men were the instruments of her policy. The Greek grammarian, Longinus, became her first minister and the Bishop of Antioch, Paulus of Samosate, declared himself in her favor. His orthodoxy was very dubious but his influence was considerable. It has never been proved that Zenobia was a Christian or even a proselyte.

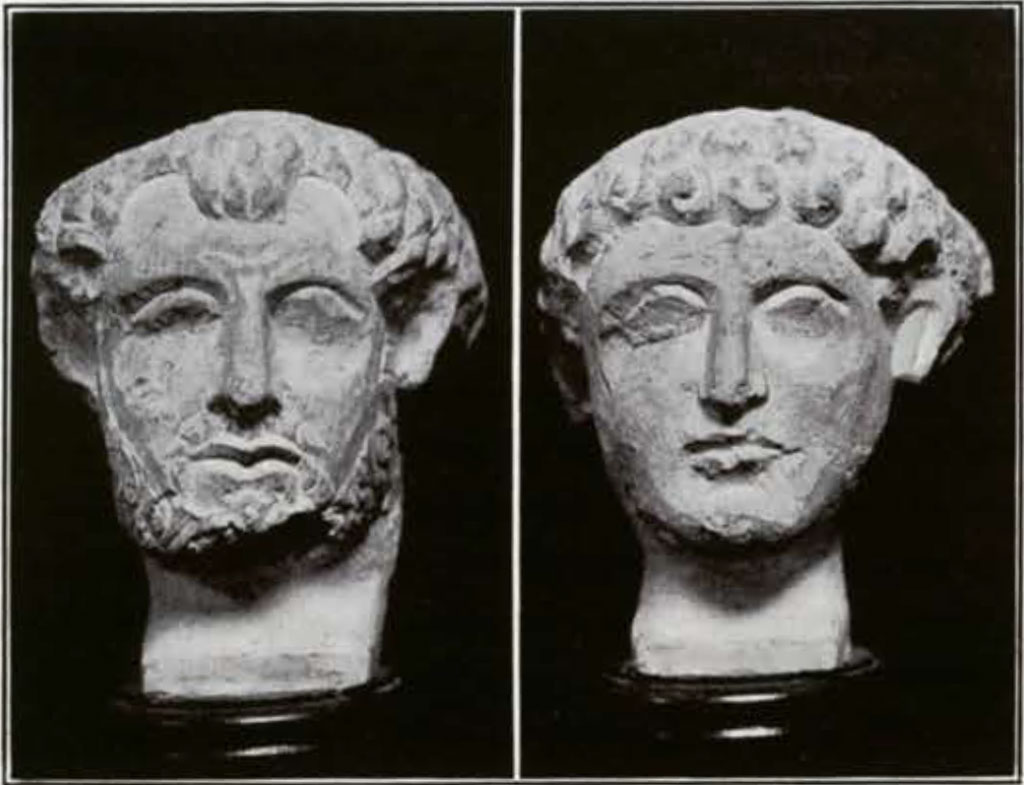

Museum Object Numbers: B8911 / B8909 / B8910

In 269 A.D., while Claudius was fighting the Goths, Zenobia thought the time was ripe for the fulfilment of her ambition. Zabdas, her general, occupied Egypt and nearly all Asia Minor. He would doubtless have conquered Bithynia also if the new emperor, Aurelian, had not compromised in A.D. 270 and stayed Zenobia’s conquests by important concessions. He acknowledged all the titles of Vahballât and her conquests and, to give to the pact public sanction, the mints in Antiochia and Alexandria were ordered to issue coins showing on the obverse Vahballât and on the reverse Aurelianus.

But what woman will ever rest satisfied with half of her dream come true? In A.D. 271 Vahballât is proclaimed “Augustus” and on the new coins the head of Zenobia replaces the head of Aurelian. Then the measure was full and the Roman Emperor decided to march on Syria and to destroy the new empire. At that moment it included the old provinces subject to Odeinat, Syria, Arabia, and Mesopotamia, to which Zenobia had added Egypt and Asia Minor, except Bithynia. Aurelian sent to Egypt Probus—the future emperor—and marched himself through Asia Minor. Egypt was reconquered in A.D. 271.

Aurelian arrived, by way of Galatia, in Tyane and pursued to Antiochia the retreating army of Palmyra. The first encounter was favorable to the Romans. The Roman cavalry was not so heavy or numerous as the Syrians but their legions were old, seasoned, unconquerable troops. Zabdas and Zenobia left Antiochia for Emese, their last line of retreat before Palmyra. Their forces still numbered seventy thousand men. The battle took place before Emese and turned into a disaster for Zenobia. The Roman cavalry played again the same tactics they had played so successfully before Antioch. The Syrian riders were heavily protected, both men and animals, by plate armour. The Roman cavalry retreated before them without fighting, till they brought them, exhausted by the pursuit, in front of the legions, who won a decisive victory. Zabdas and Zenobia with the remainder of their broken army, fled back across the desert to Palmyra, whither Aurelian followed them, harassed all the way by the nomad supporters of Zenobia. The city was well defended and a regular siege was necessary, as the inhabitants refused to capitulate. Persian help was near. It was expected at any moment, but in vain; for the Persians were beaten and forced to recross the Euphrates. Zenobia decided to leave the city and to go in person to enlist Persian support. She left Palmyra secretly. But Aurelian, aware of her flight, despatched a cavalry corps which overtook her just as she was about to cross the Euphrates. The queen was brought back to the camp a prisoner but she was treated with kindness by the emperor. A few days later the city opened its gates to the Roman troops, which collected a rich booty—A.D. 272.

The emperor left a garrison at Palmyra and returned to Antioch. At Emese he ordered the execution of some of the leaders of the revolt, among whom was Longinus. The soldiers asked for the death of Zenobia, but she was reserved for the triumph of the emperor in Rome. Her son Vahballât probably accompanied her.

Museum Object Numbers: B9187/ B9188

Image Number: 8045

But the worst was still awaiting Palmyra. Aurelian had scarcely arrived in Europe when revolt broke out again at the same time in Alexandria and Palmyra. In the last city, the Roman governor, Sandarion, and his six hundred archers were put to death and Antiochus, probably a relative of Zenobia, was made king. The wild joy of the Syrians in the last flaring up of the blaze of revolt was bound to vanish like the desert mirage. Marcellinus, prefect of Mesopotamia, sent a fast rider to the emperor, who returned at once by forced marches to Syria, entered Palmyra without fighting, and delivered it up to his soldiers for pillage and final destruction, A.D. 273. The rich and proud city never arose from its ruins. It passed out of history and after the Moslem conquest its very existence was forgotten. The crusaders ignored it. The Spaniard, Benjamin di Tudela, visited it and found a Jewish community there. When it was rediscovered by English merchants of Aleppo at the end of the seventeenth century, the veracity of their report was very much doubted.

The golden threads of legend began to intertwine with history round the figure of Zenobia. The triumph of Aurelian took place in A.D. 274 in Rome. Byzantine chroniclers tell us that Zenobia figured in the pageant laden with golden chains. The great queen who, for a while, had held in check the Roman power ended her days in a modest villa at Tibur, graciously donated by her victor.

Zenobia in all her glory must have looked very much like the elegant women of Palmyra in their best attire, as preserved in our collection of busts. She wore, probably, the same long tunic of light material—fine wool or linen?—flounced and embroidered at the neck, falling to the elbows and leaving the arms bare. The woollen or silk mantle was fastened in front of the left shoulder by a circular metal brooch or clasp, with pendants. A large veil, like the modern Syrian izâr, was thrown over the head, falling gracefully on the shoulders and enveloping the upper part of the body. But Oriental luxury triumphed in a gorgeous display of turbans, crowns, diadems, strings of pearls, precious stones, earrings, necklaces, rings, bracelets, and jewels of all kinds. The hair, waved and parted, was drawn back over a metal—probably gold—band decorated with incised patterns and cutting a straight line above the eyebrows. The hair was covered by a flat turban made of a long scarf of rich material, sometimes embroidered with rich patterns in gold and silver threads, twisted round the head or rolled like a crown. Heavy jewelled bands made of large stones set on round, oval, or rectangular metal plaques, which were strung on silk or metal threads and assembled by links, hung from above the turban, and divided in two splendid lines across the masses of undulating hair. Three round gems or pendants were attached in the middle above the eyes, like them glossy and mobile. Earrings were heavy pendants made of beads, rings, sprays of flowers, bunches of fruits. There were innumerable necklaces, strings of pearls, gold, silver, stone beads, with pendants, inverted crescents, chains with lockets and plaques, and still other pendants, arranged in tiers and falling lower and lower on the breast. The bracelets were simple and cylindrical or twisted heavy spirals with studs in relief. The ring was worn on the little finger of the left hand. The usual attitude is graceful and shows the lady at her best, one hand across her breast holding a fold of her mantle, while the other hand is raised, daintily drawing aside one edge of the veil and revealing her beauty.

Such busts in relief are excellent and true portraits of the inhabitants of Palmyra in the second and third centuries A.D. We owe them to the riches and luxury displayed by the great Palmyrene families to satisfy their vanity and secure for themselves an abode in eternity. Their tombs were of two kinds, the tower tombs lining the main entrance of the city to the west, and the rock cave tombs cut in the side of the hills, like the more familiar catacombs in Rome and the monuments along the Via Appia, the tomb of Cecilia Metella, the pyramid of Cestius, and the largest of all, the tomb of Hadrian, now the Castello S. Angelo. Their busts and reliefs within and without the tombs have their modern parallel in the funerary monuments of our cathedrals, an attempt to preserve above the decayed bones of the great a stone likeness of them at their best and a name for eternity.

Museum Object Numbers: B8908/ B9189

Image Number: 8045

The best preserved tower tombs of Palmyra are the tombs of Elahbêl and the tomb of Jamblic. The first is built on a square plan, 9.50 m. on each side, and it has two storeys. The door is surmounted by a triangular lintel resting on two consoles. At a height of 12 m. above the ground, a balcony supported by two consoles forms a kind of stone bed for recumbent and standing figures. Above the whole is a round window. The room at ground level measures 7.63 m. by 3.35 m., and is 6.43 m. high. The sides are divided into four compartments by pilasters with Corinthian capitals. Each compartment is subdivided by stone slabs into six vaults, where once rested the mummified bodies. Early travellers saw some of the bodies still there, and the Ny Carlsberg Museum in Copenhagen has the only one now known. The rest have been destroyed by Arab peddlers in their search for medicine. The ceiling is adorned with a casement pattern and white roses on a blue ground, with a central relief of three groups of four busts each, all of which are clothed in purple shirts with a white, blue, or black scarf or mantle about the neck. The back wall has five more busts of women between columns supporting an architrave. Above the architrave a sarcophagus adorned with four female busts was once surmounted by a bed and a reclining figure, now missing. A canopy resting on fluted columns surmounted the whole and ended in four bands covered with inscriptions. Other busts were placed one above the entrance and five above the small stair leading to the second floor. The second floor has the same arrangements as the first, but no decorations, and was probably reserved to poorer members of the family. While the outside walls are of a coarse gray stone, the inside walls and ceilings are of a white, smooth stone painted red. The letters of all inscriptions are also painted red. No other tomb has given us so many inscriptions. The main dedication is engraved on a marble plaque placed outside under the balcony. It reads in Greek and Aramæan:

“This tomb was built by Elahbêl, Mannai, Sokaii, and Maliku, the sons of Vahballât, the son of Mannai, the grandson of Elahbêl, for themselves and their children, in the month of Nisan, in 414 (=April 113 A.D.).”

Museum Object Number: B9186

Image Number: 8045

The largest cave tomb was not reserved to one family, but was a mortuary undertaking which provided room for more than 390 bodies in a T-shaped artificial excavation of the hillside. Groups of vaults were sold by the original owner and resold on speculation. Its interior was decorated with reliefs; also, and chiefly, with remarkable paintings on stucco, as well as with painted inscriptions giving the names of the various owners and the titles of their properties. The paintings are exceptionally interesting as representing a Greek school of painters active in Syria in the third century, whose models must have influenced Roman art and decoration long before the Byzantine school existed. The winged genii supporting a bust of Nike in a circle are reproduced in the same attitude on the old mosaic of S. Praxede in Rome.

Jews and Christians undoubtedly had communities in Palmyra.. We hear of a tomb “built forever with all its ornaments by Zebîda and Samuel son of Levi, son of Jacob, son of Samuel, in honor of Levi their father, for themselves, their brothers, their sons, and grandsons forever—April 212 A.D.” Marinus, bishop of Palmyra, was with the delegation of Syrian bishops at the Council of Nicæa. The dedication of small altars in Palmyra to an anonymous god “Whose name be blessed forever,” savours more of the Jewish tradition and ritual than of any definite Christian influence.

But it is high time to introduce in details the Palmyrene busts which are the motive and excuse for this paper.

Museum Object Number:B8907

Image Number: 8044

- Bust of a lady of quality with dresses and jewels as described above. She has her arms bare to the elbows, the right hand extended across holding the upper fold of her mantle, the left raised to draw slightly aside the edge of her veil. She wears a large supple tunic and a mantle fastened with a large round clasp on the left shoulder. Her turban below the veil is made of a rich embroidered material, with rosettes of four petals and palmettes in a network of bands with dots. The hair is parted, waved, and drawn back over a gold(?) band with geometrical incised designs. A heavy jewelled band hangs from above the turban, and divides in two above the hair. It is composed of large round, oval, or square stones, set on metal plaques, each with a line of dots around it, and mounted on five or six linked strings. Three round beads hang in the middle of the forehead. The small earrings are bell-shaped. Four necklaces hang in tiers, each with a central pendant, a round stone set in a metal ring. The lowest pendant is the largest, of oval form, set in a ring of dots which may represent pearls or small stones. The first necklace is a simple string, the second a chain, the third a string of beads, the fourth a double chain. The bracelets are large twisted spirals with studs. A ring on the left little finger completes the adornment of the lady.

Her face is of a plain round type, with large eyes, prominent straight eyebrows, not meeting, strong straight nose, sensuous lips, firm round chin, on a short and well-proportioned neck. The whole is full of energy and decision. The eyes with the outer angle slightly lifted, the high cheek bones and round cheeks and the plump arms add an Oriental charm to the regular features.

The bust is cut in high relief. The head is almost detached from the limestone block in which it is cut. The inscription on the right is spurious. Arab dealers do not hesitate to add such meaningless signs, in the hope of exacting a higher price from unsuspecting buyers.CBS. 8904. From Palmyra. 495 mm. X 370 mm.

- Bust of a lady as before. Her name is inscribed on the right in the square letters of Palmyra: “Jedî’at, daughter of Siôna, son of Peim(a). Alas!” She wears the long flowing tunic, with arms bare to the elbows; the mantle fastened with a round clasp on the left shoulder; a veil; a turban made of a twisted, folded scarf. Her hair is parted and drawn back over a metal band cutting across the forehead. The band is engraved with palms, the symbol of Palmyra, and a network pattern between bands of dots. The earrings are in the form of a small acorn. A long lock of hair falls on the right shoulder below the veil. The breasts show through the light material of the tunic and mantle. There are two simple necklaces with pendants; one is a string, the other a chain. A ring on the left little finger and bracelets(?) add a last touch to her beauty. A curtain pegged to the wall by two rosettes forms the background.

CBS. 8905. From Palmyra. 50 cm. X 44 cm.

- Female bust in relief as before. It is still more simply adorned. The right arm is muffled in the mantle thrown over the left shoulder. There is only one necklace of beads. The hair is parted and drawn back over the metal band adorning the forehead. Rosettes, between bands with dots, decorate the circlet. A veil is thrown over the light turban. The features are strong, with large eyes, high cheek bones, round, firm chin. The whole figure was probably enclosed in a circle or frame of leaves and must have been cut out of a larger relief or a sarcophagus.

CBS. 8912. From Palmyra. 405 mm. X 265 mm.

- Portrait bust of “Ma’ân, son of Bar` a, son of Zabad’ateh. Alas!” So says the inscription on the right. This man wears his waved and curled hair low on his wrinkled forehead. His eyes are large—and painted black—under prominent eyebrows. The deeply furrowed cheeks and cheek bones are evidently copied from nature. The nose is strong and straight. A short beard and trimmed moustache surround a sad mouth. The ears are large and projecting. The costume is, as usual, made up of a tunic and a mantle thrown over the right shoulder and muffling the right arm. The right hand holds the edge of the festoon in front. Another angle of the mantle hangs over the left shoulder and is held in the fold of the left arm. The left hand carries an uninscribed tablet. The little finger has a ring.

CBS. 8906. From Palmyra. 59 cm. X 38 cm.

- Funerary relief of “Malku, son of Moqîmu. Alas!” Malku is reclining on a bed; his left hand pillowed on a high cushion holds a cup. His right, resting on his drawn-up knee, holds a fruit or a flower. He is evidently enjoying what he hopes will be an eternal banquet. Two young servants standing behind hold, one a cup and a dipper, the second a two-handled vase with the good mixture. The association of death and the life beyond with a banquet is familiar to the Eastern mind. It is found on many reliefs in Greece, Italy, and Asia Minor, not to mention the parable of the wedding in the Gospel, or the words of the Lord at the Last Supper.

Malku and his servants are dressed in tunics slightly opened at the neck and decorated with embroidery in front and round the neck and lower edge. Beads, scallops, chevrons, network patterns, are found on the tunic, and on the long trousers falling to the ankle, also on the cushion and the rug covering the bed. A mantle or toga is thrown round the neck, fastened by a clasp on the right shoulder, and wrapped round the left arm. The common headdress, a cylindrical cap somewhat larger at the top, is here missing. Malku is bareheaded. His thick short hair is thrown back, waved and curled. A curtain has been pinned against the wall with two rosettes and serves as a background. The practice survives in the East.

Cup and vase are stippled and suggest metal work. The belt of Malku is loose, as becomes a man at rest, while his servants wear it tight, forming a fold.CBS. 8902. From Palmyra. 545 mm. X 445 mm.

- Young servant bringing a dish—a roast lamb—to the funeral banquet. He is dressed as above in an embroidered sleeved tunic. The embroidered patterns are rosettes, leaves, and lines of dots. The young beardless figure wears long curly hair, with masses of curls falling on the neck. The eyes are large with slightly curved eyebrows. The nose is thin and long. The cheeks form an elongated oval above a long neck marked by two folds of flesh. Spurious inscription.

CBS. 8903. From Palmyra. 535 mm. X 365 mm.

- Head of a woman. Same style of turban, jewels, and headdress as before (No. 1). The head has been cut out of a larger relief.

CBS. 8910. From Palmyra. 240 mm. X 185 mm.

- Head of a woman as above (No. 3). The gold band above the forehead is decorated with a palm between two bands of beads. Cut from a larger relief, so that part of the hair on the right is missing.

CBS. 8909. From Palmyra. 215 mm. X 170 mm.

- Head of a woman as above (No. 3). The band above the forehead is decorated only with vertical lines. Cut from a larger relief.

CBS. 8911. From Palmyra. 23 cm. X 17 cm.

- Head of beardless young man. Cut from a larger relief.

CBS. 9188. From Palmyra. 19 cm. X 15 cm.

- Head of a beardless young man. Cut from a larger relief.

CBS. 9187. From Palmyra. 185 mm. X 130 mm.

- Head of a man with short beard and moustache, and a tuft of hair hanging in the middle of his forehead, which is marked with a few wrinkles. Cut from a larger relief.

CBS. 8908. From Palmyra. 95 mm. X 90 mm.

- Head of a beardless young man. Cut from a larger relief.

CBS. 9189. From Palmyra. 95 mm. X 90 mm.

- Beardless head. Bust in a circular frame decorated with long tongues or leaves. The youthful figure wears a tunic and a mantle thrown over the left shoulder. Cut from a larger relief.

CBS. 9186. From Palmyra. 115 mm. X 105 mm.

- Relief representing a chained dog, or rather a leopard, to judge from the spots, the powerful claws and teeth. The hair is treated conventionally, showing a heavy growth behind each limb and round the neck. A strong ring on the back united two straps, one round the neck and the other round the body, which served to secure the wild creature. It is pictured on a frame of beads and curved leaves.

CBS. 8907. From Palmyra. 395 mm. X 350 mm.

Dr. Harald Ingholt of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen, the museum which is richest in Palmyra sculptures, wrote on December 14th, 1925, to the late Dr. G. B. Gordon: “During my work in Palmyra this spring, I discovered a sarcophagus in one of the tombs with a representation similar to that of No. 8907 in the University Museum.”

1Cf. Choix d’inscriptions de Palmyre, by J. B. CHABOT, Paris, 1922, our best guide to Palmyra.↪