THE forested lowlands of the present Guatemala, Yucatan, and adjacent parts of southern Mexico and northern Honduras produced the highest expression in America of the religious impulse, the greatest development in intellectual, artistic, and architectural achievement. But, unlike the Aztecs and the Incas, the zenith of the culture of the Maya had passed by the time of Columbus, the cities had been largely abandoned and the older ones were already lost in the forest. Conquered twenty years later than the Aztecs, their subjugation was an anti-climax that attracted slight attention. No golden treasure rewarded the conquerors. In the intervening years, pestilences introduced by the first shipwrecked Spaniards, civil wars and natural calamities had greatly reduced the population. No Prescott has made the name and achievements of the Maya known to every schoolboy, yet they stood preeminent in America in the fields of writing, astronomical knowledge, calendrical accuracy, art, architecture and stone sculpture.

The Maya reached the summit of their civilization in the lowland regions of northern Guatemala (the Department of Peten), British Honduras, and Yucatan, with a slight extension into southern Mexico and northern Honduras. In the adjacent highlands of Guatemala lived and still live a number of nations of kindred blood, speaking allied Mayan languages, who enjoyed a similar basic economic and intellectual life but who apparently had not carried the latter to the same pinnacle as their eastern lowland neighbors.

Museum Object Numbers: NA5898 / NA5900 / NA5903 / NA5897 / NA5899 / NA5986

Image Number: 19524

The history of the lowland Maya falls roughly into two periods, the data upon it into two categories. The earlier “Empire” centered in the heavily forested region of the Peten, but the great “cities” were abandoned centuries before Columbus, and our sole knowledge of them is derived from the spade (or more truly the trowel and brush) of the archaeologist; no references, or only the vaguest allusions to this period, are found in the later Maya traditions. Of the “Late Empire” Maya in Yucatan, however, the accounts and legends written down by the earliest Spanish invaders, some of them word for word in the Maya language but in European characters, afford a detailed record, with recognizable names of persons and places, and dates. The latter, however, are given in the Maya calendrical system. Even a few of the native books have survived, only three however, as compared with a much larger number of Mexican codices.

The origin of the Maya and of Maya culture is still a moot problem. The popular feeling, so generally met, that no native American Indian could have achieved the cultural progress that the Maya did, and that therefore they must have had an extra-American origin, carries no conviction to archaeologists. The more fundamental and permanent factors of physical type and language must be accorded greatest weight. Physically the Maya were and are American Indians. There is some evidence that the earliest Maya, in a primitive state of culture, may have come from further south; at any rate they were in contact on their southern border with less advanced peoples of basically South American culture. The most recent opinion on the language, however, is that it is one of the southernmost members of a great linguistic family that is more strongly represented in the western United States. As regards their cultural achievements, there is no element that betrays even presumptive evidence of Old World origin, or that is not explicable as a special and higher development of the general Middle American pattern.

The remains of the earliest sedentary agricultural peoples in the Maya area are tentatively dated at a century or two before the beginning of the Christian era, about contemporary with similar early beginnings in the other regions of later higher cultures in southern and eastern Mexico. The earliest known pottery, like that in the Valley of Mexico, is simpler than the later forms, but by no means primitive, and thus presumably not of local invention.

Museum Object Number: L-16-381

Image Number: 19373

In the Maya area, and only in this area in America, the archaeologist is aided in his historical estimates by dated monuments. These dates are more accurate than most of those with which Old World archaeologists have to deal, since, for a period of over five hundred years, they record the total of elapsed days since the beginning point of the Maya count of days, and are therefore exact to a day; in most other parts of the world dates are given with reference to some local event, such as the reign of a king, and generally only in terms of years. Unfortunately the correlation of the Maya calendar with ours is still a disputed question, but most students agree on one day-for-day system of correlation. Several alternative systems differ by about 260 years, or multiples thereof.

The earliest recorded date on a monument in the Maya region, at the ruined Maya city of Uaxactun in the forests of Peten, Guatemala, is, according to the correlation most generally accepted at present*, 328 A.D., but the founding of the city is estimated at several centuries earlier, about the beginning of the Christian era. Since apparently earlier dates are found in the Olmec region further north, the oldest so far found, at Tres Zapotes, Vera Cruz, being tentatively read as 31 B.C., it is possible that the cultural impulse came from that presumably older region.

Within the next few centuries dozens of cities sprang up in the Peten region. While their exact dates are still controversial, their relative dates, periods, and minimum spans of occupancy are known by the dated monuments. Some were founded late and apparently were occupied only a short time; Uaxactun contains both the earliest and the latest supposedly contemporary dates known in this region, indicating an occupancy of at least six hundred years. The most important and best-known cities are Uaxactun and Tikal in Peten, Guatemala; Copan and Quirigua to the southeast, near the Motagua River, Copan being in present Honduras; and Piedras Negras, Palenque, and Yaxchilan on the Usumacinta River to the west, the latter two being in Mexican territory. These are all modern names, the former native designations being entirely unknown.

Museum Object Number: L-16-382

Image Numbers: 19221, 19222

Uaxactun and Tikal are rarely visited, though the airplane now makes the trip comfortable and quick. Uaxactun is famed for its early-period pyramid, stucco-covered and adorned with awe-inspiring masks; this was completely excavated by the Carnegie Institution. Tikal, as yet untouched by the archaeologist, is the most impressive site of all, with its many ruined temple-crowned pyramids, the tops of which tower above the tallest trees of the enveloping forest, one of them to a height of 175 feet. Copan and Quirigua are among the most accessible sites, the former by airplane, the latter by railroad. Both are notable for their sculptured monuments, stelae and altars. These are the most profusely and flamboyantly carved of any in the Maya region, and those at Quirigua are also the largest, one of the stelae standing twenty-seven feet above ground, thirty-five in total height. Copan, with its quantities of monuments and altars, inscriptions, courts, terraces and buildings, is one of the largest sites and probably the best known. The buildings at Palenque and Yaxchilan are among the best preserved in the Old Maya region, and have been partly restored. But these Usumacinta River cities were distinguished especially for the admirable art shown in the stone carving and stucco work, art that need not shrink from comparison with any of the world’s sculptures, ancient or modern. (Figures 1, 16, 20, 21)

Piedras Negras

Piedras Negras, excavated by The University Museum from 1931 until 1938, largely by the Eldridge R. Johnson Expeditions, may be taken as a typical “Old Empire” Maya city. The remains of the masonry buildings, of course, represent only the ceremonial center; immediately surrounding these is a zone of house mounds where the priests and nobles probably lived. On the periphery and throughout the countryside, close to their farms, more humble houses, made of perishable materials, sheltered the common people.

The masonry buildings were probably never used for habitation. Several leveled courts of considerable size are surrounded by edifices on platforms or pyramids varying in height, each of which had been enlarged several times. These had interiors of rubble, facings of roughly shaped stone, and a surface finish of plaster, made from native limestone. The pyramids are sometimes free-standing, but hills were partly covered with buildings on terraces. Buildings of four main types are distinguished: small independent structures, commonly termed “temples,” generally of one room, with few doorways and usually set on a pyramid; larger buildings with more rooms and doorways, on broader bases and often in groups, commonly termed “palaces,” though it is doubtful if they were used for residence; small buildings with interior fireplaces obviously used as sweat-baths; I-shaped flat courts between two parallel structures that were certainly used for the playing of the ceremonial ball-game. (Frontispiece)

Museum Object Number: 38-14-1

Image Number: 19562, 45372

Early Maya architecture was massive, as the craft was in its infancy; in fact, the earliest buildings at Piedras Negras did not have masonry roofs. The Maya, like all American Indians, were ignorant of the principle of the true arch, and the rooms, when roofed with masonry, were narrow and covered by a peaked “corbel arch” in which each higher stone projected a little beyond the one below. The walls and ceilings were thick, and the core hold together with mortar so that the structure was stone-faced concrete. The mass of the masonry was often greater than the area of the rooms. In later years, as confidence was gained and technique perfected, the thickness of the walls was decreased and the size of the rooms enlarged. Certain of the “Late Empire” buildings are quite light with large rooms, and some had flat roofs of beams and mortar. Most of the “palaces” contained “thrones,” either of solid masonry or of a table type, on which, apparently, a priest sat during certain ceremonies. (Figures 16, 20)

On the low terraces in front of the temples, stelae or upright carved monuments were erected. These were apparently to mark the passage of time, to accompany ceremonies connected with the calendar, or possibly to record prophecies of future events. At Piedras Negras they were erected almost every five years during a period of three centuries. The front, and sometimes the back also, was usually carved with figures of deities or ceremonial scenes, and the narrower sides were generally filled with hieroglyphs that give, among other data, the date.

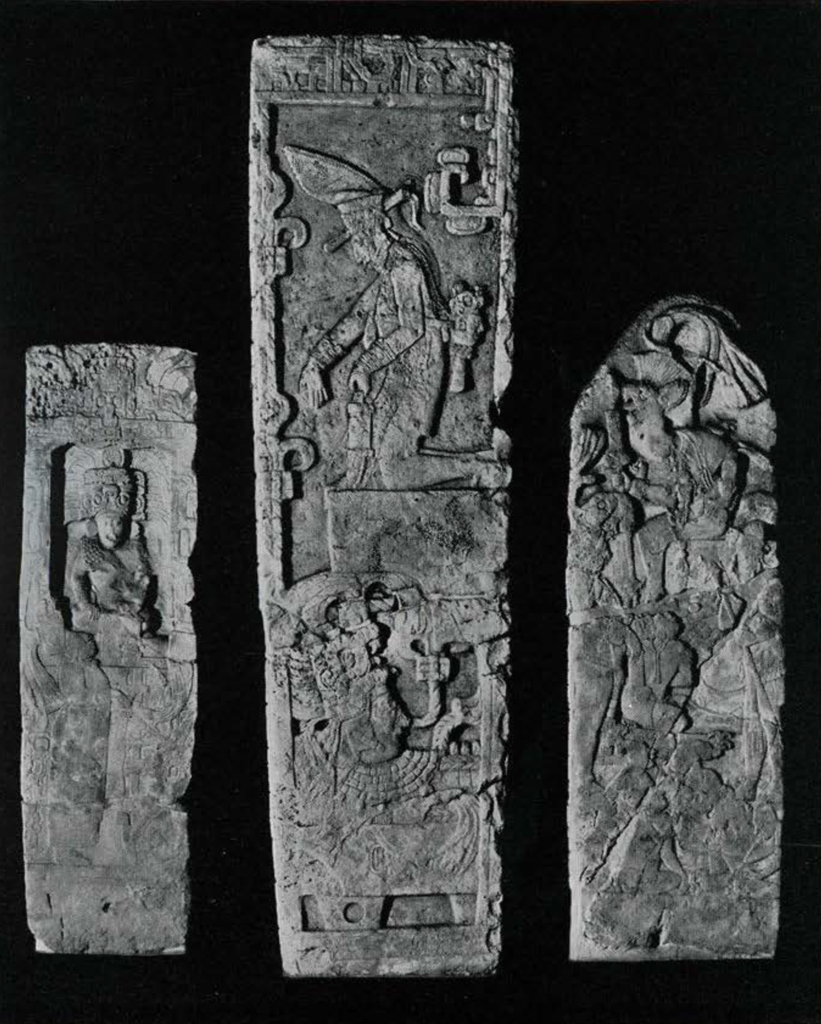

The lush tropical forest naturally overran all these ceremonial centers or “cities” as soon as they were abandoned, and the roots of the great trees tore the edifices apart. Piedras Negras for some reason suffered especially, and only a part of one building still retains a roof. The stelae too all toppled over, the tropical rains of a thousand years eroded the exposed faces and have damaged the others since they were turned over when they were first discovered nearly fifty years ago. To save them from further deterioration and to afford more persons an opportunity to see these masterpieces of aboriginal American art, a number of the most artistic monuments were taken out and sent, on loan, to The University Museum, and others to the Archaeological Museum in Guatemala City. (Figure 21)

All the Maya cities in this region were deserted by about the year 900, and some of them, judging by the dates on the last monuments, several centuries earlier. Probably the ceremonial centers were first abandoned but the people continued to live on their farms. Eventually, however, the entire population apparently died out or migrated, and left the land nearly unpopulated, as it is today, traversed only by gatherers of chicle for American gum-chewers. When Cortes crossed the country in 1525 he made no note of having seen or heard of any of the old cities. Many theories have been propounded to explain this abandonment, most of them based on economic grounds. The most probable reason, however, is the same as that which caused the downfall of the later Maya cities in Yucatan, as well as of most of the great civilizations of antiquity in the Old World, warfare and civil strife. Probably the people, weary of the yoke of the priesthood with the interminable demands for building and ceremony, revolted. At Piedras Negras, at any rate, the archaeological evidence definitely indicates that the ceremonial furnishings were intentionally damaged, the monuments mutilated, and the ceremonial center abandoned. Whether the present virtual extinction of the population had an economic or a social cause is unknown.

Former theories held that, after the “Old Empire” cities were abandoned, the people wandered for several generations until at last they “discovered” and colonized Yucatan. Recent discoveries indicate that cities existed in Yucatan throughout the older period, but probably were not large or important. At any rate, after about the year 1000 the center of lowland Maya higher culture changed its focus from Peten to northern Yucatan where sprang up the “New” or Second Maya “Empire.” Of this we have detailed historical information from the native legends and chronicles. Many new cities were established and former ones enlarged. Three large centers, Chichen ltza, Uxmal, and Mayapan, became dominant, and the history of the later Maya is largely that of these cities and their “lords.” The details of alliances, intrigues, perfidy and strife need not be recounted. Mayapan was finally conquered; only mounds and scattered broken monuments mark the known site today. Uxmal was abandoned, but the buildings, purely Mayan in architecture, remain in good condition to astonish the modern tourist; some of them have been restored.

Chichen Itza has become the Mecca of visitors to Yucatan because of its magnitude and the excellent state of preservation of the edifices, many of which have been restored by the Carnegie Institution and the Mexican Government. The sacred cenote or well into which offerings and human sacrifices were cast, and from which many of the former have been recovered, appeals to the imagination of the visitor. The city had a long and interesting history. A few hieroglyphic dates indicate that it was occupied in the days of the Old “Empire”; later it became one of the major ceremonial centers. About the year 1200 it was conquered and, either then or shortly before the Spanish Conquest, was abandoned. In the last few centuries of its habitation, influence from Mexico, probably under a group of Toltecs from Tula, was predominant, and a number of structures of a type of architecture showing Mexican influence were built in a new sector of the city. The Castillo, the Temple of the Warriors, and the immense Ball Court belong to this period. These have been restored to a semblance of their former glory, as have others, apparently earlier in age and more essentially Mayan in type.

Presumably all of the Maya cities were independent, neighboring ones at times allied, at other times at war. The cult of human sacrifice was apparently but weakly developed and there was not the same urge for constant formal warfare that characterized the Aztecs. The common people tilled their crops, relying mainly on maize (corn), and, in the off seasons, obeying the orders of the priests and “lords,” labored on the masonry edifices and took part in the ceremonies performed in them. For, as in highland Mexico, the government was a theocracy. They had no domestic animals except the dog, the turkey, and stingless bees; no wheeled vehicles, no metal. Even gold was unknown to them until a very late period, and always rare. Every few years, as the fields became filled with matted weeds, they had to fell and burn a section of the forest for a new farm. This primitive “milpa” system of cultivation is still used by most of the Indians of Middle America. Though the system is simple and primitive, it is by no means inefficient. Agronomists believe that it is the system possibly best fitted to the country and produces about the maximum possible yield. Ordinarily the men wore little clothing, but for dress occasions wove fine garments of cotton with decorations in many colors. The art of pottery making was highly perfected with a great variety of shapes, techniques and decorative methods, each characteristic of a definite area and period.

The outstanding achievements of the Maya were, as we have said, in intellectual and esthetic fields rather than in mundane and militaristic ones. They were the only people in America who developed a system of graphic record that was more than pictographic, though the highland Mexicans had made a beginning at it with simple pictorial symbols representing definite numbers, and compound symbols for proper names. The Maya glyphs, which have not the least resemblance to Egyptian or any other system of hieroglyphs in form or meaning, were evidently pictorial in origin but had become so conventionalized and stylized that in few cases is the meaning apparent. They were, therefore, on the way to becoming a true system of writing, though by no means yet phonetic or alphabetic. Most of them are compound forms of several elements, and there was no rigid standardization so that there are thousands of minor variants, many of which variations may have no significance. The meanings of only a small proportion of these glyphs are known, but those that can be interpreted recur most frequently. These identifiable glyphs all refer to calendrical, astronomical and arithmetical data, and thus only the calendrical content of most inscriptions can be understood. It is probable that the entire purport of the inscriptions, especially those on the carved monuments, is calendrico-astrological. In some portions there may be an approximation to true writing, expressed in rebus form, as in Mexican proper names. This is especially true of the native written books or codices, only three of which have survived. Among the others, quantities of which were destroyed by the early Spanish clergy, it is probable that some contained historical traditions and other mnemonic data.

The Maya calendar was very complex; together with their epigraphy, astronomy and arithmetic, with which it is intimately bound up, it has engaged the researches of many specialists. It included a ceremonial period of 260 days, a year calendar, a lunar calendar, a Venus calendar, and possibly other planetary calendars. The periods of apparent revolution of the heavens (the year), of the moon and of Venus had been observed, calculated and averaged with care. It has been claimed that the error in the 365-day Maya solar calendar was calculated almost as accurately as we should do with the formulae of our modern system of leap-days, and that the error in their average moon calendar did not amount to a full day until passage of 300 years. These claims can hardly be said to be definitely proved as yet. But there is definite evidence that the Maya knew that on the average the time from one new or full moon to the next was something more than 29 1⁄2 days, and calculated that 365 days for one year falls short a full day every fourth year. The system used in England until 1752 was no more accurate than this and made no allowance for the minor error in this leap-day rule which amounts to less than a day a century. Whatever the degree of Maya accuracy attained, there is good reason to believe that it was accomplished without the aid of the modern astronomer’s clocks or of instruments for accurately measuring angles. The early Maya habitually recorded the passage of time by elapsed days from a fixed starting point, August 13th, 3113 B.C., according to the correlation most generally accepted, but the later Maya, so far as we can be sure, confined this day-count to a period of about 260 years.

Museum Object Number: NA11216 / 12702 / 37-13-144 / 12683

Image Number: 19550b

Maya art finds its expression in architecture, sculpture and carving, molding, painting and weaving. Of the latter the humid earth has left us hardly a single example, but the depictions of textiles in the carvings, as well as the historical accounts, indicate that it was of a very high quality of technique and art. The other arts are all associated. All masonry was covered with a plaster finish which was tinted with various colors, probably as were the stone sculpture and stucco. The colorful effect of the ceremonial centers must have been most impressive. The edifices, and especially the high “roof-combs” above the temples, were profusely decorated with figures, masks and decorative elements of colored stucco. On the interior walls mural frescoes showing battles and other scenes of action were painted in many colors. Painting and drawing were also employed in the native books or codices, and on most pottery vessels. (Page 1)

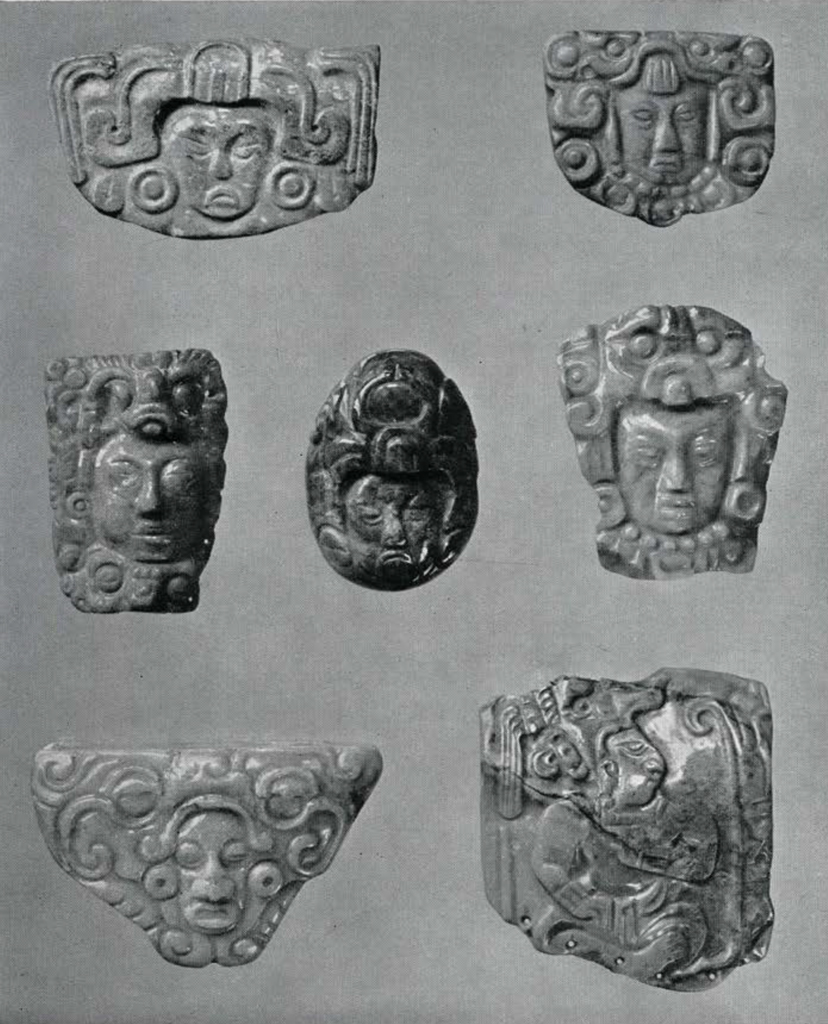

Carving was done in wood and stone. Naturally few of the former have been preserved, though a few carved lintels of hard wood still in place indicate that the wood carving was on a plane of excellence equal to that in stone. Small objects were carved of bone, shell and especially of jade. The latter was the material most prized by the Maya, as by all aboriginal Middle Americans. Jade, it must be remembered, is harder than steel, and the task of shaping it into pendants, generally with human or godlike faces, with nothing but stone tools, abrasives, time and patience, was most arduous. (Figures 18, 19)

The artistic achievements of the Maya are best exemplified and best known by the large stone monuments, the stelae and altars, tablets, lintels and thrones. Figures of gods or of mythological animals play the major role in sculpture. Most of the monuments, such as the best-known stelae from Copan, give a barbaric, though powerful impression to those of us accustomed to the classical European art tradition. In most Maya sculpture there is little placidity and few plain surfaces, every part being covered with detail. In the cities of the Usumacinta River Valley, however, and especially at Piedras Negras, the sculpture need not defer to any of the great art schools of the ancient world, whether in composition, sureness of line, perfection of proportions, grace, freedom, technique, attention to detail, or such effects as foreshortening. (Figures 16, 20, 21)

Museum Object Numbers: 12696 / 37-13-200 / NA11531 / 37-12-44A / 37-12-44B

Image Number: 19558

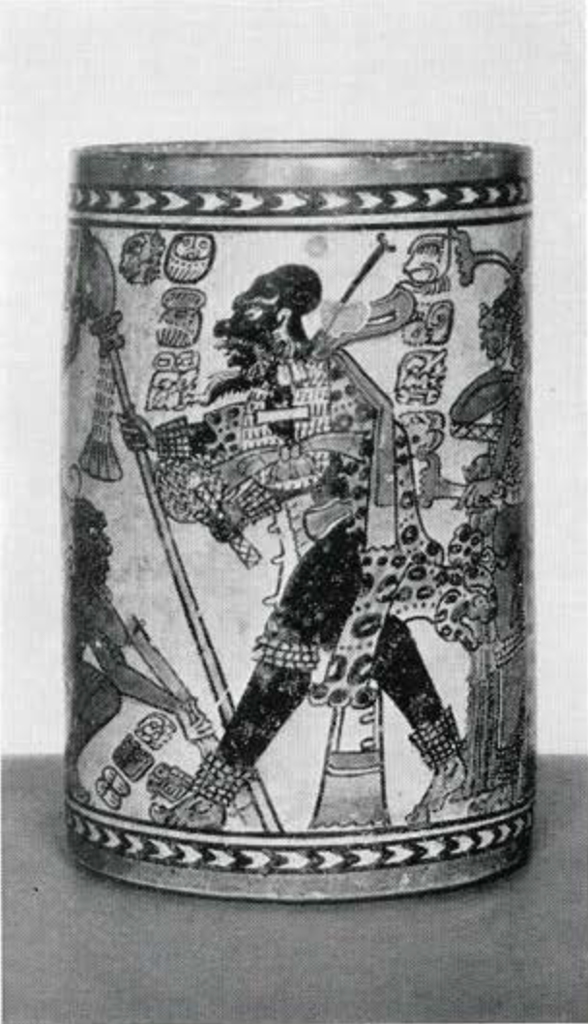

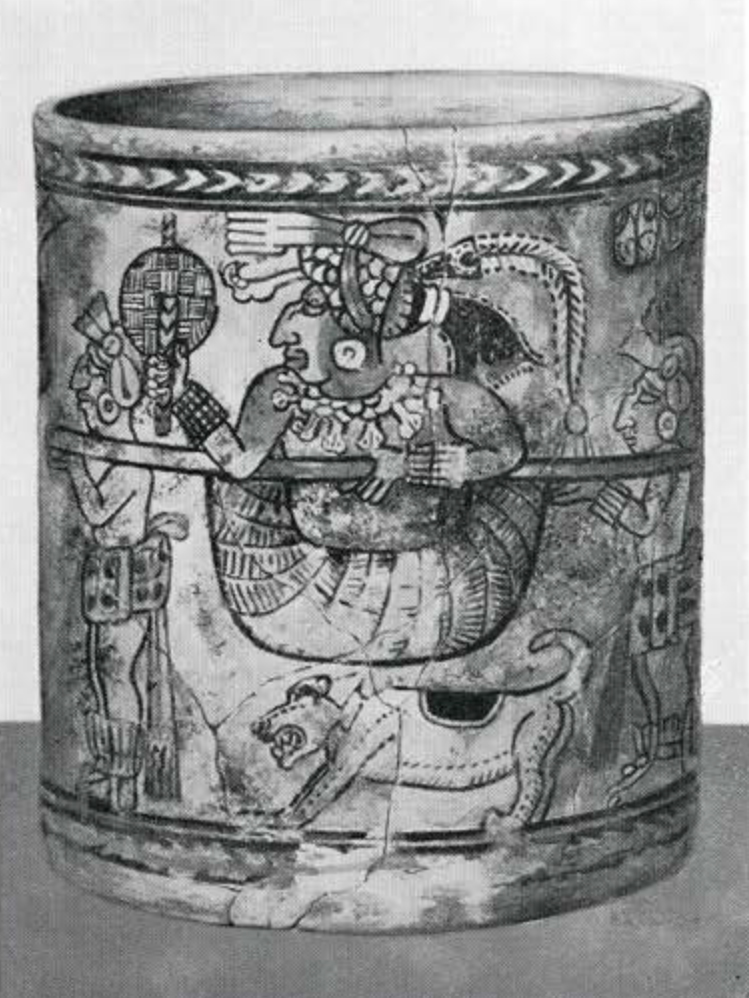

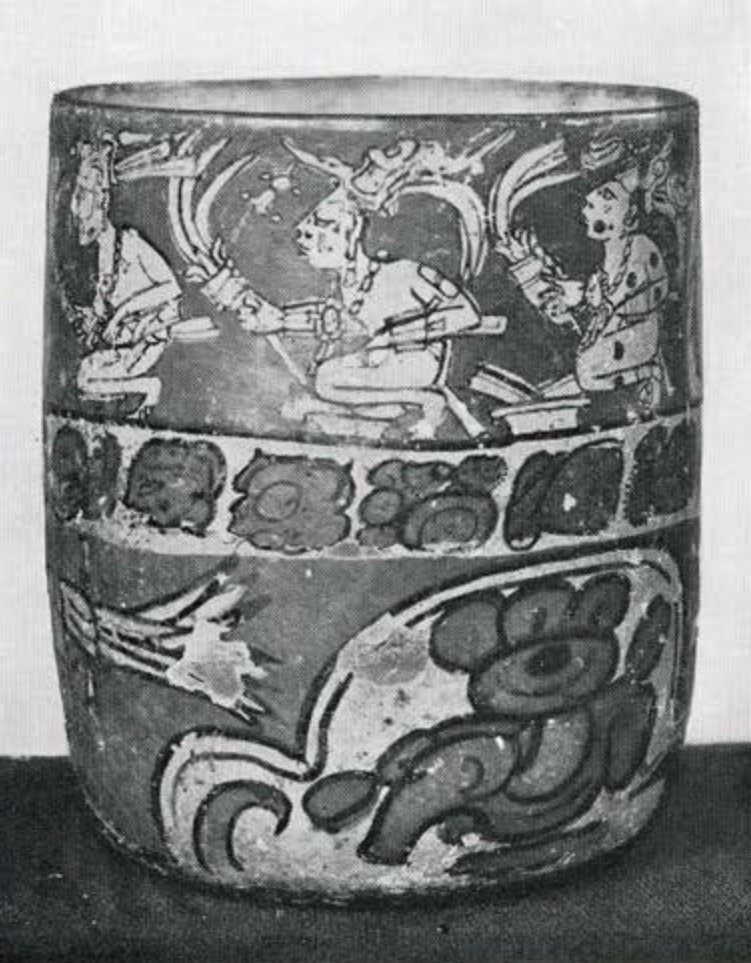

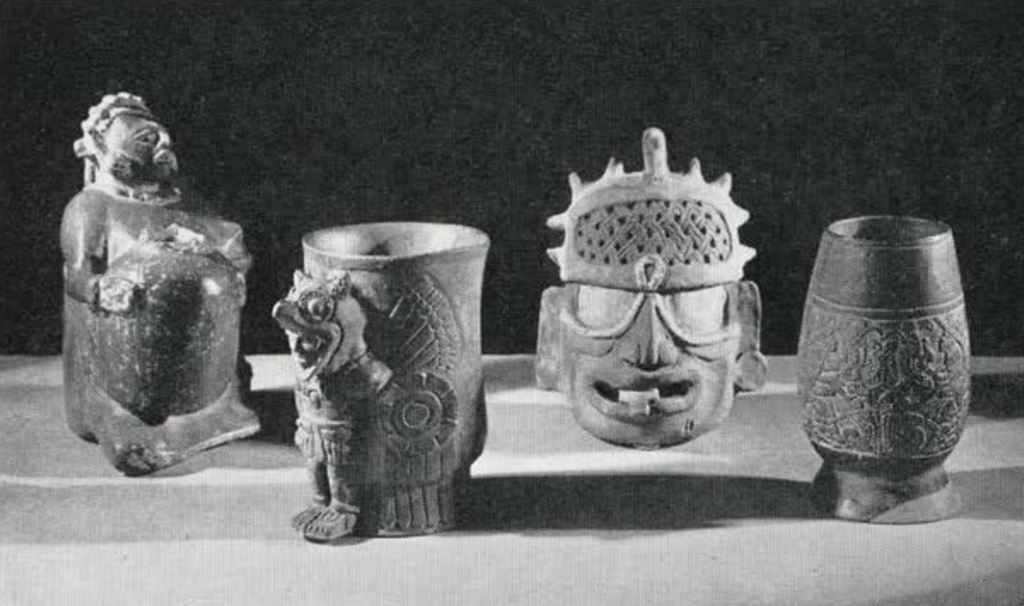

As everywhere in America where ceramics played a large part in the national economy, the art of pottery making rose to the rank of a major art. In addition to figurines and many other small utilitarian and art objects of pottery, vessels of almost every conceivable shape and method of decoration were manufactured, each region and period having its peculiar types. Two wares deserve special mention, effigy vases in naturalistic forms with a quasi-glaze surface known as plumbate ware, and simple large cups of cylindrical shape painted with pictorial scenes in many colors. The former are of a late period; the best examples of the latter come from the department of Alta Vera Paz in the Guatemalan foothills. (Figures 17, 22-24)

The ancient peoples of the Guatemala highlands, the Quiché, Cakchiquel, Zutugil and many other groups, spoke languages related to those of the lowland Maya and had a similar calendar and theology, but were inferior to them in masonry architecture and stone sculpture, and, if we may judge from the apparent absence of stone inscriptions, they lacked writing. Living in cool regions, their basic economy must have been somewhat different. Their manufactures of ceramics, small stone carvings, textiles and other products, each of its own special type, attained as high a level as those of any other people in Middle America. Among the important archaeological sites in the Mayan highlands are Zacualpa, Utatlan and Kaminaljuyú, the latter a large ancient “city” in the present suburbs of Guatemala City, recently excavated by the Carnegie Institution. (Page 2)

The Pacific slope of Guatemala was inhabited by the Pipil, a people speaking a Nahua language related to Aztec. Their archaeological remains, such as the colossal stone heads and the delicately sculptured stone “yokes,” obviously link them with the “Olmec” region on the Atlantic coast in southern Vera Cruz. The best known of their sites are Cozumalhualpa and Baul. The highlands and the Pacific coast of Guatemala have been but slightly investigated to date, but researches are now being vigorously pursued in this important field.

* The Goodman-Thompson-Martinez correlation. All dates herein are in this system which is roughly 260 years later than the Spinden correlation. ↪