ARCHÆOLOGISTS in the field have many hard days, but they have also a delightful reward when out of the trenches come new documents which throw light on the past, dispose of old theories and help to rebuild a truer history. One of the best pieces of sculpture discovered at Ur by the Joint Expedition during its Fourth Campaign was the head of a girl in white marble with inlaid eyes of shell and lapis lazuli, a very important monument which forces us to modify our whole conception of Sumerian art. There is here not only an extraordinarily finished delicacy of technique but an ideal of beauty not hitherto found in the same degree in the early sculptures of Mesopotamia.

Before 1881 Sumerian art was practically unknown. Our first knowledge of this ancient civilization dates from the methodical classification by León Heuzey of Sumerian monuments from Lagash in Mesopotamia in the Louvre Museum. Sumerian sculptors for fifteen hundred years before the days of Abraham and the Amorite kingdom of Babylon had been busy carving statues, statuettes, bas-reliefs and plaques out of shell, limestone, alabaster, and soft and hard diorite. One by one their monuments entered the museums of the Old World, which long remained incredulous both of their antiquity and of their artistic value. Careful publication and minute study, however, have left no room for doubt. There is a group of eight statues in the round, some of natural size, representing the patesi Gudea, a Governor of Lagash in B.C. 2400. The style and technique represent a coherent and well determined period of the sculptor’s art, an epoch in the archæological field. The master sculptor has now left the primitive stages far behind and can attack hard stones with a sure hand and positive knowledge.

Museum Object Number: B16228

Image Number: 9555

We may distinguish three classical periods of Sumerian sculpture: the Sargon and Naram Sin period, about B.C. 2600; the Gudea period, about B.C. 2400; and the Third Ur Dynasty period, about B.C. 2200. The Sargon and Naram Sin period is named after the kings of Agade, who founded a great empire. Their riches and power found natural expression in great artistic monuments. They belonged to a Semitic race named Akkadian, after their capital Agade or Akkad, a city not far from Babylon. They lived in the northern part of Mesopotamia, and mixed with the Sumerians, emulating their earlier attainments and improving their formulæ of art. Their monuments, statues, and bas-reliefs are comparable with the best sculptures of Lagash in the Gudea period, but their modelling is finer, their proportions are more elegant, and they have in large scenes a more spirited sense of composition. Their masterpiece is the stela of victory of king Naram Sin, representing the king and his troops pursuing his enemies to the summit of the hills. The enemies fall prostrate under his feet and beg for mercy. The king stands in a noble attitude in full armour, with weapons in hand, stops the pursuit, and spares the last survivors.

Sumerian art reaches its full development in the Gudea period. It then becomes remarkable for simplicity of attitudes, for a sober and even severe style realized in large smooth surfaces on reliefs and statues. The sculptors have attained a national type of workmanship very different from the Egyptian. They are less preoccupied with proportions and they show a greater originality in details. Their statues are often short and thick set, with heads too large for the bodies, but the modelling of the nude parts, in spite of the hardness of the stone, the minute chiselling of hands and fingers, is very close to nature. The eyes are large, with straight and deeply cut eyelids slightly drawn upwards in the outer corner. The eyebrows are prominent, outlined by a deep furrow above and below, and their twin arcs always meet above the nose. These heavy joined eyebrows give strength and color to the face and are characteristic of Sumerian art, though Assyrian and Persian sculptors treated eyes and eyebrows in the same manner.

Museum Object Number: B16228

The eye sockets are in many cases deeply incised and hollowed to receive an inlaid eye made of a piece of shell. The iris may be a piece of black bitumen or of blue lapis lazuli. The Egyptians used paste or coloured stones in the same way. Large eyes of chalcedony, onyx, or carnelian, some of them bearing a cuneiform inscription, presented by the Cassite kings about B.C. 1400 as votive offerings in the temple of Nippur, were not all destined for use as inlay, but were inspired by the same old Sumerian tradition. Even the Greek chryselephantine statues combining gold and ivory are not independent of Eastern influence.

The noses of statues are generally broken, but when preserved they are usually found to be almost straight, or only slightly curved, with a rounded and rather large tip. The chin is small and firm. The cheeks are framed in a short oval with well marked cheek bones, akin to the Asiatic type found also in Syrians, Jews and Armenians.

The short proportions so noticeable in the Sumerian sculptures are especially marked in the massive necks, large chests, and round shoulders, with shoulder line attached very high below the ear. An expression of dignity and force redeems the awkwardness of the stumpy figures.

The common attitude of many statues of standing or seated worshippers with their hands clasped, the right in the left, expresses the respectful immobility of the Oriental servant awaiting the orders of his master. Many a statue bears a votive inscription engraved on the sides of the throne, or even on the garments, across the shoulders or round the knees of the figure. Such statues were commonly deposited in a sacred place in front of the statues or emblems of the gods. Their attitude, even in the smallest statue, is a religious one. They are votive offerings to remind the gods of the good deeds of the ruler, and to obtain a special blessing on his life and posterity. Unlike the Egyptian sculptor aiming at the material likeness which was so important for the cult of the dead, the Sumerian sculptor produces impersonal heads of a conventional type.

Museum Object Number: B16229

Image Number: 8439

Feminine statuettes are not rare. They were not excluded, as they generally were by the Assyrians. The severe Sumerian artist succeeded in his efforts to express feminine grace by a progressive attenuation of the national type to a point where the close resemblance to the Greek type is very remarkable. The same Greek feeling is noticeable in the first study of the folds, relief and arrangement of the garment attempted by the Sumerian sculptor. It is quite unknown in Egypt and Assyria.

This refinement and softening of the Sumerian type is especially evident in the third classical period, that of the Third Ur Dynasty, about B.C. 2200. The progress of schools of sculptors and the development of artistic taste had naturally brought about a change from the archaic types, where square and angular forms betrayed the original plan, by way of the progressively less severe forms of the Gudea period, to the smooth, slim, rounded forms of the third period, which aimed more and more at elegance.

Before the three classical periods representing the artistic efforts of a mixed population of Sumerians and Akkadians, must be placed an archaic, more purely Sumerian period, before B.C. 3000. No one who has studied the stela of the Vultures, the most important monument of this period, will ever mistake or forget the early Sumerian type with enormous curved nose, receding forehead, large almond shaped eyes, broad ears, short neck and wide chest, angular elbows, head all shaven and shorn, except in the case of the king and the god, finally the remarkable garment in the form of a woollen flounced petticoat, with thickly set hanging lappets in imitation of a fleece.

The small collection of stone heads, statuettes and reliefs here presented belongs to the best periods of Sumerian sculpture between B.C. 2600 and 2100. They were discovered by the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and our Museum, by the Museum’s Expedition at Nippur, or they were acquired by purchase. With the exception of the sculptures, which, in the division made by the Governments at Constantinople and at Baghdad, were not assigned to the Museum, the monuments are the property of the Museum and will take high rank in the Ur room between the great stela of Ur-Nammu and the archaic statues and reliefs of Tall-al-‘Ubaid. They will allow, for the first time in this country, a close view and study of the wonderful Sumerian art which surprises many and leaves the imagination marvelling at the beginnings of civilisation.

Museum Object Number: B16229

Image Number: 8441

I

The White Marble Head With Inlaid Eyes1

The small head of a girl with long undulating hair hanging over her shoulders and confined about the temples by a thin scarf, rolled like a coronet, is the gem of the collection. The eyeballs are inlaid, consisting of a piece of shell originally white but now turned gold-brown with age. The irises are small discs of blue lapis. The vividness of the colors adds to the charm of the deep sunken eyes and gives life to the small round face with its quiet, thoughtful look. Inlaid eyes of blue lapis were previously known to have been used for the decoration of the figures of animals—of a bull’s head in copper and a lion’s head in stone—but they are seen here for the first time applied to a human head.

The head was found in 1925 at Ur, within the limits of the temple towards the southern angle, in ruins dating about B.C. 2190, when the kings of Larsa were lords of Ur, but it is not otherwise connected with the ruins. It is an example of the beautiful, simple work of the best period, about the time of Gudea. The simple crownlike headdress, the long undulating hair simply parted, passing over the ears and covering the neck and shoulders, are distinctive notes in the costume of Sumerian women of that period. A five-row necklace encircles the rather short neck.

The great surprise is to find in the delicately carved and beautiful face so close an approach to the ideal Greek type. The eye. brows are prominent, meeting above the nose, and they are emphasized according to the Sumerian rule, but the Oriental expression has been tempered with a gentle grace. The large almond shaped eyes are beautiful and natural, and are drawn upwards at the corners with the slight affectation of most of the heads of the Gudea type. The small chin and rounded oval face are quite charming, and so also are the parted lips of which faint traces remain. The nose is broken as usual. We can only conjecture that it was almost straight, with a slight curve at the end, as in the small “Longperier” statuette of the same style in the Louvre.

Museum Object Number: B16229

Image Number: 8442

The statuette when complete must have represented, as the Louvre statuette does, a young girl seated on a cubiform throne, with her hands modestly clasped on her breast or holding a round ampulla full of perfumed oil, a symbol of the prayers and offerings which were the prelude to a ritual sacrifice before the statues of the gods. The long floating hair of Ishtar, goddess of love, is the distinctive mark and privilege of the higher class: kings, princes, and princesses, and also of the high priestess, who is generally a sister or daughter of the king. Her statue as a worshipper placed in the temple before the statue of the god was a votive offering for the life and the long and happy reign of the ruler. In the same manner the young Samuel was devoted by his mother to the service of the God of Israel. An inscription on the throne may have formulated the votive prayer and defined the memorial purpose of the statue, as we shall see in the case of the monument next described.

II

The Black Diorite Statue of Ningal, the Moon Goddess2

This statue has been restored from many fragments found in 1926 scattered among the ashes and on the pavement of the Ningal temple at Ur. The enemies who destroyed this delicate work of art were not the Elamites, the hereditary enemy from the eastern border, but newcomers in the Euphrates plain, the Amorites of Babylon. A Semitic race like the Akkadians, they hated the Sumerians of the south, and had no rest until they had broken their spirit of independence, destroyed the walls of Erech and Ur, and opened for their own profit the trading road toward the sea. The plundering of the temple and the cruel destruction of the monuments erected by former kings were invariable incidents of these military expeditions. About the same time Abraham and his family left the desolated city and moved north to Harran, a junction of the caravan roads, where the Moon God had another sanctuary and trade was more prosperous.

This small female figure sitting with quiet grace and dignity

on her square throne is not only an extremely delicate piece of work, but is invaluable as a well dated record in the history of art in Sumeria. On three sides of the throne is a long inscription recording the dedication of the statue by Enannatum, the high priest, son of Ishme-Dagan king of Isin, who rebuilt the temple of Ningal. The statue, therefore, was carved within ten years of B.C. 2080.

The figure of the goddess has still that beautiful simplicity of attitude and refined elegance imparted to feminine statuettes since the Gudea period. She is dressed in the best court style. Her long floating hair is confined by a simple diadem, and she wears a long woollen tunic of material known as Babylonian kaunakes. Long hair and a garment of kaunakes are always confined to gods and kings. The statue is most likely a figure of the high priestess, the daughter of the king and the personification of the Moon Goddess on earth. Her hands are clasped, the right in the left, in an attitude of respect. Nails and fingers are carved in minute detail. This humble attitude need not surprise us. All statues with a votive inscription were placed in a sacred place, facing the images of the gods or their symbols. This one is a votive offering for the life of the king. Above the diadem six (1) copper nails still fixed in the original stone show that a mitrelike ornament probably of gold or of copper gilt adorned the head of the statuette. The mitre with one or four pairs of horns is the traditional emblem of divinity and would prove this figure wearing it to be that of the goddess herself. The respectful attitude of the clasped hands is not exclusively reserved to servants but might express the submission of Ningal to her husband, the Moon God. It is found in other statues of goddesses, as we shall see in the next two examples. Only Ishtar is represented as a queen and a warrior, armed with bow and scimitar or holding ring and scepter. The older Sumerian goddesses play the minor parts of faithful wives and chatelaines in charge of the cattle, the fish pond, the poultry yard, the pantry, and the cellar.

Enough was left of the statue of Ningal to allow a complete restoration to be made. The crown of the head with a line of hair over the eyes and the ears is original. Part of the base and of the skirts, both elbows, the right shoulder, and the lower part of the face are restored. The missing face was the most disappointing defect in the statuette. It has been happily restored and copied from a beautiful Sumerian statue from Lagash in the Louvre, which was named, after the headdress, “la femme a l’écharpe” and is probably contemporary with Gudea and also an example of the best classical period. Perhaps the neck ought to be a little shorter, as well as the lower jaw, the chin more prominent, and the oval of the face not quite so refined. But these are minor defects in a reconstruction otherwise true to the original type, in which we may enjoy the beauty and harmony of the work of art without undue archæological scruples.

The tunic worn by the goddess and made of the special woollen material, the kaunakes, is frequently represented on cylinder seals but not so often on statues. It represents not a flounced garment but, in a conventionally symmetrical way, a material with long hair woven in imitation of the natural fleece of animals. The hair of the kid presented by a worshipper (the fragment of sculpture illustrated on page 246), is arranged in the same conventional way. The hanging lappets of wool are disposed in zones following the lines of the weft, as in the modern Greek floccata. It has long hair only on one side. The rectangular shawl of kaunakes thrown over the left shoulder was worn by gods and goddesses and persons of high rank. On the present feminine statue it is made like a tunic with sleeves. In Assyria and also in Persia floccata is reserved to the gods. In Greece it is often a sumptuous covering on festival couches.

The thick masses of hair of the goddess fall low on her shoulders in lovely curls in truly royal style. The two shorter curls resting on her breast in front in pre-Victorian fashion have been copied from the statue next described, which was discovered in the same part of the ruins in the Ningal temple. They are usual in the representations of the goddess Ishtar, and have a juvenile grace of their own. The necklace of five strands is due to the same inspiration, as well as the loose upper border of the tunic resting modestly and naturally on the shoulders.

The bare feet of the goddess rest solidly on the ground and, so far as they are represented, are a scrupulous imitation of nature, true to the smallest details. In statues representing a standing posture, the fore parts of the feet only are carved, within a small hollow, in order to avoid the breaking of the statue by a too great weakening of the base. This is a Sumerian invention, just as legitimate as the trunk or support adopted by Greek sculptors. In seated figures, the feet and the lower parts of the garment are free on either side, but the heels are still engaged in the cuboid block out of which the seat of the goddess is carved.

The seat, in its severe simplicity, has style and elegance. Seat, legs, and rungs are a fine development of the plain cubiform seat of earlier statues. Knobs of metal protect the feet and raise the seat above the ground. Their ellipsoidal curves make a pleasant contrast to the straight lines of the rest of the seat. The flat panels are filled with the inscription, which respects the limits of the frame with the delicate restraint and sense of harmony of true artistry.

The copper nails still visible round the base show that it was decorated with applied ornament, a band of metal or engraved pieces of shell. Two holes beneath the base were used to fix it on a pedestal. A rectangular hole cut within the neck and visible before the reconstruction suggests that the head was carved separately and fixed on.

The Museum has in this small statuette a very good example of Sumerian art. The next, and in this case a complete statue, was retained by the Iraq Museum in Baghdad. It was discovered at the same time and place as the fragments of the Ningal statuette, and represents another familiar goddess.

Museum Object Number: L-29-214

III

A Diorite Statue of the Goddess Bau3

This small squat figure as soon as discovered at Ur became familiar among the Arab diggers as “Mother Goose,” because of the four geese, two of which support her feet while two flank her throne. This is not a real but a symbolic seat, formed by three mighty undulations of the waters of the Euphrates. Does not the Lord Chancellor in England still sit on a sack of wool for a reason connected symbolically with his high office?

Bau is the wife of the god Ningirsu, the patron of Lagash, a city forty miles north of Ur on the great cut, the Shatt-el-Hai, joining the Tigris and the Euphrates. The old city is on the border of the marsh land, a paradise for all kinds of water fowl, but especially for ducks, geese and pelicans. While her husband was a great warrior and bore in his coat of arms the eagle, the famous Imgig bird of Lagash, Bau was concerned with fowl of a humbler sort, those which served as food.

The fame of our little goddess spread rapidly. Local sheikhs left their mud palaces to pay her a visit in the camp. Notabilities and boy scouts from the nearest town came on special tours to see her till the Iraq government became aware of her existence and claimed her for its Museum at Baghdad, as one of the oldest representatives of the land and as a work of art rare for the completeness of its preservation.

The attitude of dignified respect expressed by the clasped hands is the same as in the Ningal statue. Identical is the tunic of kaunakes, with sleeves and seven zones of thrummed flocks, the necklace of five strands, the bare feet, the pendent Victorian locks. The short neck and massive head are very characteristic of Sumerian art, which was not too much preoccupied with actual proportions. They recall a very squat statue of the patesi Gudea now to be seen intact in the Louvre. We must reconcile ourselves to that disregard of true proportions, which, however, did not shock the Sumerian artist.

Museum Object Number: L-29-214

The real difference from the Ningal statue is in the fashion of the headdress and in some technical details in the carving of the face. The eye sockets are hollowed and prepared for the inlay, which is missing. The nose was carved separately and is also missing. We may suspect that it was cut to repair an accident to, or a defect in, the stone. The headdress is not a simple diadem but a scarf covering the top of the head and rolled about it like a coronet. The long hair, except for the two curls in front, is not allowed to hang loose, but is tied in the back into a matronly chignon. The short neck shows below and the shoulder blades are carefully modelled under the thickness of the woollen garment. The same pre-Greek sense of folds in the garment is visible in the curve of the back and below the arms. The naive primitive charm of the statuette is scarcely marred by the plumpness of the figure.

IV

A Headless Statue from Nippur4

The headless statuette from Nippur, of which we have only a photograph, is of the same style, but much coarser in execution. The attitude of the seated figure with the hands clasped, the sleeved tunic of kaunakes, the cuboid form of the throne, the bare feet not completely disengaged from the block, belong to the same age and tradition. The statue, as far as one can judge from a photograph, seems to have been cut in soft limestone and not in diorite. The drawing of the fingers and the undulating lines of the kaunakes show a carelessness which we might expect in the poorer material.

The main interest of the figure is derived from the obvious symbolic meaning of the quart and pint pots with which her throne is decorated. We know that in the temple of Lagash there was a cellar of the best mountain wines. We have lists of the red and white wines of the plains, hills, and mountains from the cellars of King Nebuchadnezzar, and the German excavators suggested that the vaulted cellars below the so-called hanging gardens of Babylon —one of the wonders of the world—must have been the coolest place to preserve the sealed jars. Four types of pots are represented on two sides of the throne. There must have been two other types on the third side of which we have no photograph. One is a round cylindrical vase. Alabaster vases of that form, with a cartouche of the name of the Moon Goddess, have been found at Ur and are preserved in the Museum. The second vase, the unit of measure called by the Sumerian a qa, is very interesting for its conical form. Placed in the hands of the gods, full of perfumed oil, if not of choice wine, it was a symbol of prayers and offerings, rich in meaning. The second and third vases are larger receptacles well represented in our collections of pottery from Ur and Nippur. Whether theyare standard measures or have some other special purpose has yet to be established.

Museum Object Number: B8960

V

A Woman Worshipper Wearing the Fringed Shawl5

This miniature work, brought from Babylon by Dr. J. P. Peters in 1890, is one of the early acquisitions of the Museum. It is also an exquisite piece of Sumerian art. The modelling of the body, neck, throat, shoulders and of the back below the shawl belongs to the best period after Gudea, when severe simplicity was tempered with grace and elegance very close to the ideal of Greek art. The little statuette is cut in soft limestone of a very fine grain. For harmonious proportions and delicate womanly charm it can compare with two beautiful statuettes of the same style, “La femme a l’écharpe” from Tello, and an ivory statuette from Susa. It was entered in the catalogue of the section—C.B.S. 8960—with seven other pieces, as bought by order of Dr. J. P. Peters, through the Arab Obeid, on July 1, 1890, for 311 piasters, and was said to come from Babil. It is high time that this charming Sumerian lady should be presented to readers of the JOURNAL.

She has the traditional attitude of the worshipper standing in front of the god, with hands clasped, awaiting orders with respectful dignity. Her type is decidedly Oriental, with slightly curved nose, round cheeks, fleshy lips, and the generous lines of full-blown womanhood. The eye sockets, deeply sunk, were prepared for inlay according to the ancient tradition which aimed at greater lifelikeness of the face through a bright contrast of colors. The eyebrows were made of a colored paste laid in a deep arched furrow. The same technique is seen in old terra cotta masks where eyes and eyebrows were of black bituminous paste inlaid. The same taste for polychromy may explain why the back of the head of the statuette is flattened beyond the true proportions and besmeared with bitumen perhaps in imitation of a mass of dark hair. Or an artificial wig and mitre like a crown were perhaps added and fixed with bitumen on the head. The bright metal and the dark hair would have combined in a very happy effect. A deep groove cut on the back in the form of the letter Y with a hole at the meeting point of the three branches suggests the fixing of an artificial ornament behind. The commonornaments, a necklace of four strands and bracelets showing a similar disposition of four rings soldered together, are cut in the stone in low relief.

Museum Object Number: B16665

Image Number: 139229a

The elegance and simplicity of the dress deserve attention. It is no longer a tunic of kaunakes with sleeves, of that best material reserved to gods and goddesses. The long rectangular shawl left intact as it came from the loom is draped about the body with surprising sculptural effect. It is spread in front across the breast, passing below the arms, and is crossed behind, with the two extreme angles thrown over the shoulders and hanging in front where they are held by the folded arms. The result of such drapery on the living model is charming and resembles very much the mode of wearing the Spanish shawl in the country of its origin. Safety pins or fibulæ may have contributed to the security of the whole adjustment. The fringes are the thrummed ends of the warp. Embroideries have been added to the sides of the weft. The long furrow below the left arm may have been cut afterwards for some inlaid ornament or for making repairs; or it may indicate a natural opening of the shawl as in certain statuettes from Lagash and Susa.

VI

A Daughter of Sargon, High Priestess of Ur6

This disk of calcitic alabaster, round like the full moon, with a bas-relief on one side and the remains of an inscription on the other, is an important monument of art and history. The relief shows a sacrificial scene. The high priestess in her best flounced dress presides over the ritual libation poured on the altar by the shorn and shaven priest. She is followed by two other priests carrying palms (?), a staff of office (?), and probably a pail of holy water. The streams of liquid are received in a large hourglass-shaped vase, placed on the lower tier of a pyramidal stepped altar. Five steps are still visible. The scene is a reproduction of a ritual act in the temple, probably on a special feast day, when the full moon was on high over the ziggurat in the first hours of the night, and, we may conjecture, in spring when the palm trees are in bloom. Why not in a palm grove when the eve was cool? Texts are known ruling that the king himself must perform this rite under such circumstances. The whole composition has the simplicity and elegance of a Greek “theory” or sacred procession. Though badly mutilated, the piece shows a high degree of artistic skill and a real bas-relief technique. Each figure is drawn separately with a complete value of its own on an open field, but is connected by gesture or attitude with the single religious action. The proportions are natural, even elegant, and lack the clumsiness of some of the squat figures of the Gudea period.

The inscription on the back completes the value of the monument. It records its dedication by En-hedu-anna, high priestess of Ur, wife of the Moon God and daughter of Sargon, king of Kish. It is our earliest and a well dated monument. In this survey of Sumerianart, it ought to come first as representing the first classical period. That the high priestess should be at the same time wife of the Moon God, playing on earth the part of Ningal, is a welcome piece of information, linking together the chain of evidence. The last king of Babylon, Nabonidus, installed his daughter as high priestess at Ur, thus restoring a tradition going back to another high priestess, sister of Rim-Sin, king of Larsa about B.C. 2000. Two hundred years earlier, Me-Enlil, a daughter of king Shulgi, may have occupied the same position of high priestess. This is certain in the case of the daughter of Sargon about B.C. 2600. The same interpretation must apply to the archaic limestone bas-relief, published in the MUSEUM JOURNAL, September, 1926, with details such as the entire nudity of the priest, which belong to a very primitive period before B.C. 3200. For nearly two thousand years we can follow and assist at the daily ritual at Ur as it was performed long before and after the days of Abraham. We can see with our eyes the role played by the high priestess, a daughter or sister of the king, presiding over the ritual acts performed by the shaven priests attached to the house of the Moon God. The princess is also the wife of the Moon God, she can reveal his secrets and deliver oracles in his name. She truly unites in her person human and divine powers. And we must not be surprised to see a king of Babylon, Adad-apal-idinnam, claim a close relationship—emu, father-in-law—to the Moon God. Many kings of Larsa before him were raised to the glory of beloved husbands of Ishtar.

The high priestess En-hedu-anna wears the sleeved tunic of kaunakes well befitting her as Moon Goddess on earth. Her long hair hangs down her back and three braids rest on her breast. A crownlike diadem made of a rolled scarf (?) is tied about her head. Her right hand is raised to the level of her face in token of adoration. Her left hand is too much mutilated to show whether she carried a staff or sceptre. By rare good fortune the small fragment of her head was recovered in the ruins of the Ningal temple at some distance from the other fragments which were all scattered over the pavement of about B.C. 2100. The rounded nose, thick lips, large almond eyes, and deep incised eyebrows of the feminine Sumerian type are preserved here better than in the marble head with inlaid eyes.

Museum Object Number: B16665

Image Number: 190621

The libator priest wears a tight linen tunic which probably passed over the left shoulder, leaving the right arm and shoulder bare. He holds with both hands clasped round the foot the vase with a long spout which was used for the libation. This is a traditional type of sacred vessel and a traditional gesture. The hourglass-shaped vase in many cases had green palms and bunches of dates planted in it ready to receive the stream of water. The altar with five steps is a new model of the stone altar with a ledge known from ancient seals.

This monument, now the property of the Museum, was discovered at Ur in 1926. Each figure of the relief is 9 mm. high.

VII

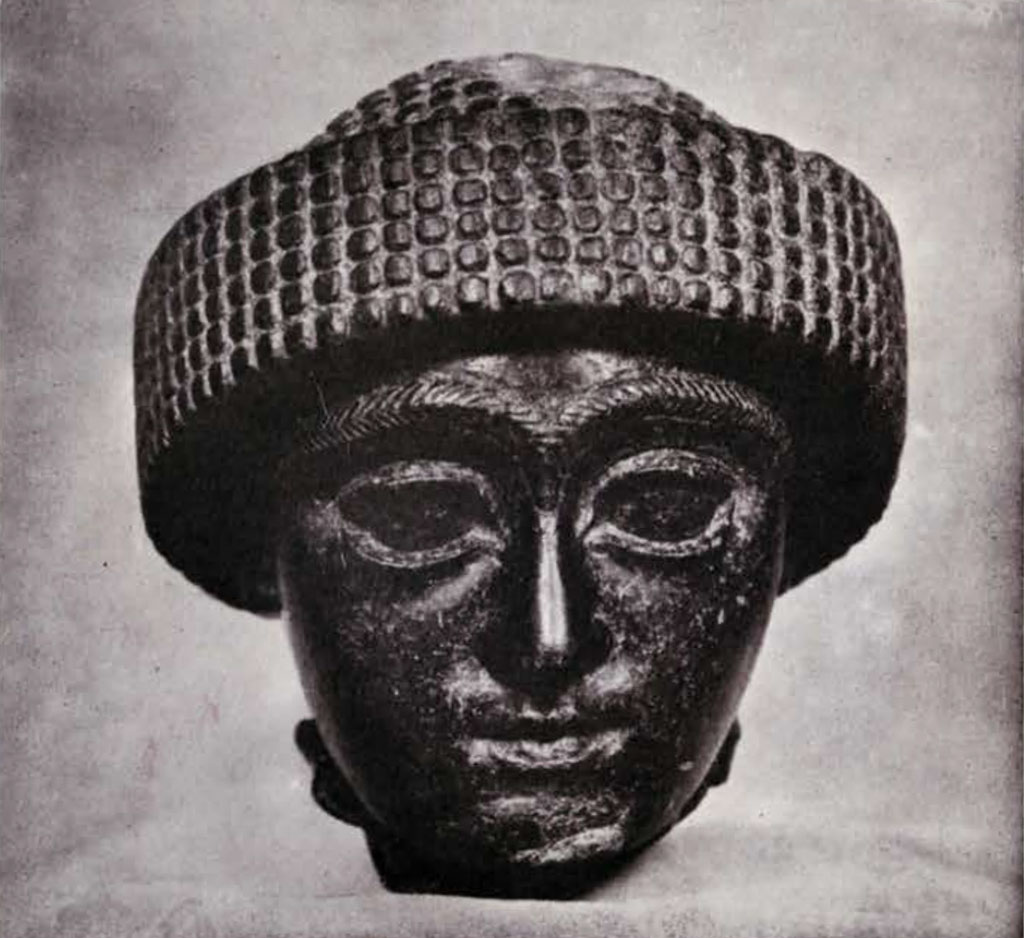

A Diorite Head of Gudea7

This new example of the classical turbaned head of the famous governor of Lagash is a happy addition to the small collection of statues in the Museum. It was acquired from a dealer in antiquities and was reputed to have come from Tello, the modern site of Lagash. It is well preserved, the nose is intact, which is a rare piece of good fortune among so many mutilated heads.

Museum Object Number: B16664

Image Number: 7770

Gudea was a great ruler and a great patron of art. He had a love for that high form of art, sculpture in the round, and caused statues of himself to be cut by the dozen in hard diorite and placed as memorials in all the shrines and chapels of his pious city. Inscriptions are carved on the front, back, or sides of such statues and on the garments or on the seat, each devoted to a special god or goddess and containing graphic, ritual, mythological and sometimes his-torical details which explain their purpose and help us to hear the very voice of the past. Of course all these statues were not carved and erected at the same time, but represent different periods in a long reign. Despite the school conventions of the Sumerian type, an attempt at portraiture is obvious. Some heads represent the young Gudea, some belong to his mature age. His attitudes are also diversified. He is seated or standing, with his hands clasped, or holding on his knees the famous plan drafted with the rule and stylus of the architect on a large soft clay tablet.

The history of these statues and of their discovery forms an interesting chapter of Sumerian research. They were practically the first monuments which revealed to the world, about 1880, the importance and achievements of the old Sumerian school of sculptors. Eight statues, four seated and four standing, some of them a little over life size, were found in the same part of the ruins, in the same court and anteroom where they had been assembled, more than two thousand years after Gudea, by the last local ruler of Lagash shortly before the Christian era. His name was Adadnadin-ahe. In his inscriptions he used both the Aramaic and Greek languages, as the modern inhabitant of Iraq uses Arabic and English. His collection of statues is now the glory of the Louvre Museum. Unfortunately, not one of these statues was found with its head intact and the few heads with or without turbans which were then recovered in the ruins did not fit the bodies. Not until 1903 was a body found to which a turbaned head discovered three years before was exactly fitted, and archaeologists had the satisfaction of seeing a complete Sumerian statue. The result was rather disappointing, the squat figure being disproportionately short and the head much too large for the body. The beautiful modelling of the head, hands, feet, and of the nude parts in general, the first known attempt at representing folds in the garment, and the masterly technique in the cutting of hard stone compensated in a certain degree for the disregard of proportions.

Museum Object Number: B16664

Image Number: 7771

Another important discovery of statues of Gudea, of his son, or of a successor, apparently assembled in one room, was made in Lagash two or three years ago by Arabs digging secretly. They found their way into the European and American markets and were acquired at considerable expense by various museums. The best statue of Gudea, and a complete one, with a turbaned head, is now the pride of the Glyptotheca Ny-Carlsberg in Copenhagen. A statue of Ur-Ningirsu, son of Gudea, has been added to the Louvre collection. It has no head, but is cut in a rich brown gypseous alabaster and has a remarkable base decorated with figures in relief of bearded servants presenting offerings. Another statue of the adolescent Gudea with head, but no feet, and dressed in an elegant embroidered shawl has been published by Scheil and appears to be in private hands in Belgium. A fourth statue of Ur-Ningirsu, high priest of Nina at the time of King Ibi-Sin, seems to have found its way to Berlin. Like the statue in the Louvre, it has no head. The Gudea head recently published by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, most likely originating from Lagash, was bought in Baghdad between 1865 and 1870 and was in Ireland in private hands for many years, ignominiously used to keep a garden door open. This and the University Museum head are the first two examples to be exhibited in this country of these wonderful Sumerian sculptures, while the Louvre will long remain the treasure-house of Sumerian art with its nine large size statues, four separate heads, and over twenty statuettes.

Museum Object Number: L-29-212

The style of the diorite heads of Gudea is well known and has been minutely studied. We may sum it up in a few lines. The whole work is sober, even severe, is cut in hard stone, and still shows the primitive plan, with an attenuated grace. The eyes are large, almond shaped, with eyelids deeply incised and drawn upwards, by a peculiar mannerism, towards the outer angle. They are, however, straight and not Mongoloid. The eyebrows are prominent, arched, underlined, and meet above the nose. The nose is surprisingly straight and approximates the Greek profile. The mouth is well formed and small, like the short protruding chin. The rounded cheeks are almost oval, with well marked cheek bones which give strength and character to the face. The quiet dignity of the features is tempered by a placid smile. The governor of Lagash has nothing of the imperious warlord of Assyria. His traditional authority rests on a religious basis, the patesi being father of the city and high priest in the temple. That is why his head is shaven like those of the rest of the priestly community. The freshly shorn scalp is covered with the woollen turban so characteristic of the Gudea period. The mass of the headdress has been simplified and reduced to a symmetrically folded contrivance surrounding his temples. The surface shows a multiplicity of minute round reliefs disposed in the squares of a regular chess-board tracery. The round reliefs, generally decorated with a spiral, represent a kind of chinchilla or embroidered cloth. The general aspect suggests the modern Astrakhan cap of Persia. But no one who has an experience of the torrid climate of Lagash would think for a minute of wearing a fur cap in that region.

VIII

Head With a Turban Found at Nippur

Another head of the Gudea type was found at Nippur during the Fourth Expedition but was not assigned to the Museum. It was entered in Haynes’s diary on the first of August, 1899, as follows: “Work on the Temple Hill. A small head of a statuette of the Tello type, with turban on the head, showing the general kind of kefieh as the Arabs wear today in a different manner, was found near the east corner and also near the position of the torso found in 1896.” We have two photographs (Nos. 19 and 496) of it which were taken in the field.

The technique is much the same as that of the preceding head, but with softer lines of eyes, nose and eyebrows. It represents a more juvenile type. The nose is perfectly preserved. It is short and straight. The eyes are drawn upwards at the outer angles, the eyebrows meeting but less marked than usual. The stone must have been diorite, but this is not stated.

Museum Object Number: B12290

IX

Worshipper Offering a Lamb or Kid

This fragment of sculpture was found, probably at Nippur, during the Fourth Expedition. At least we may so conjecture from a photograph of it preserved among others taken in the field, but there is no number attached to it, and no other record connected with it. It is especially interesting for the conventional treatment of the hair of the animal offered—kid or lamb—by the worshipper. The disposition of the hair in regular zones justifies the interpretation of the woollen kaunakes as material woven in imitation of a fleece. The right shoulder of the worshipper and traces of his right arm holding the lamb are still visible. Arm and shoulder were bare, as shown by the folds of the garment drawn across below the right breast. This is the traditional attitude of the worshipper presenting an offering of an animal and a copy of the same type is found on many terra cottas. The long ears of the animal suggest a kid rather than a lamb.

The long forgotten Sumerian artist will now have his place in our collections. His great antiquity and wonderful achievements will raise a new standard in the history of civilisation, pose a new problem of the origin and transmission of that celestial fire, the “mens divinior.” “En prona mutantur in annos. Prima cadunt . . .” But is not art a perennial fountain of youth?

1Height 95 mm. C.B.S. 15228. Ur Field Catalogue 6782.↪

2Height of the restored statue 24 cm.; width at the elbows 105 mm.; base 12 x 10 cm. C.B.S. 16229. Ur Field Catalogue 6352. Restored by Miss M. L. Baker.↪

3Height 29 cm. Ur Field Catalogue 6779.↪

4Probably from the Fourth Nippur Expedition. Photographs Nos. 224, 225, 226.↪

5Height 87 mm. C.B.S. 8960.↪

6Diameter 265 mm. C.B.S. 16665. Ur Field Catalogue 6612.↪

7Height 10 cm; width of the turban 83 mm.; ear to ear 6 cm. C.B.S. 16664.↪